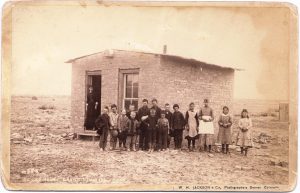

Grand Junction’s second school building [1880’s]. Photo by prominent Western photographer William Henry Jackson, courtesy of the Museums of Western Colorado.

While students in larger towns like Grand Junction or Fruita had schools with more than one room and teachers for each grade, most rural communities had only one or two-room school houses. In those rural schools, children from every grade between 1st and 8th sat together in the same room, and one teacher might have to teach 30 or more students from several different grades. Teachers often had just passed the 8th grade examination and were barely adults themselves. For instance, Eva (Wood) Leslie began teaching in Glade Park just after her graduation at Fruitvale High School. Even town schools would usually hire only one teacher for each grade, no matter how many students were enrolled in that grade.

Students could be wild and disruptive in those days, just like today. Teachers sometimes had a difficult time keeping farm and ranch kids in their seats, and were allowed to spank and hit children to keep order. The cat o’nine tails, a length of rubber hose cut into nine pieces at the end like a whip, was often used to spank children, usually boys, who got in fights or got too rowdy. Not every teacher used corporal punishment, but many did.

Grand Junction’s Lincoln Park School building, built 1925, and currently occupied by Grand River Academy.

There were rural schools on the Grand Mesa, on Glade Park and Pinon Mesa, and in many areas around Mesa County, such as Highpoint, Hunter District, Fruitvale, Mt. Lincoln, Whitewater, Appleton, and Pomona. Often, each school or group of schools had its own school district. In schools like Tope Elementary School, where teacher Ruth Larson was also the principal, the teacher might have to leave the classroom to handle a truancy or discipline problem. In these instances, an older student would step in and teach the class.

The principal at the Clifton School combined fun and discipline. According to one-time student Oscar Jaynes, the principal at Clifton would keep an eye on the boys on the playground throughout the school year. If he noticed that one boy had a problem with another boy, then at the end of the year, he would have them put on thick boxing gloves and fight it out in the “squared circle.” According to Jaynes, the gloves were thick enough that no one got hurt, fathers were present, and the boxing matches took place in a spirit of fun that allowed the boys to let off steam. Oscar Jaynes’ opponent in the ring was none other than future Colorado Supreme Court Justice James Groves, son of Mesa County Oral History Project interviewees John and Olive Groves.

To find out more about education in rural and town schools, check out the Mesa County Oral History Project and read the excellent book In the Beginning: A History of the Districts and Schools that Became Mesa County Valley School District Number 51 by Albert and Terry LaSalle.