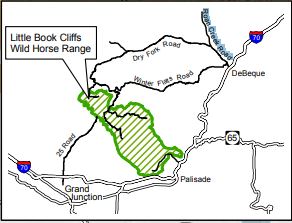

Tucked back behind the prominent sandstone face of Mt. Garfield and the sprawling Book Cliffs of Mesa County, there lies a place of desolate solitude called the Little Book Cliffs Wild Horse Range. Although it is certainly lacking in human dwellers, the dry and dusty landscape is home to a band of wild horses who have been roaming freely since the beginnings of Mesa County’s known history. According to an article written by David Wheeler from the Journal of the Western Slope:

Tucked back behind the prominent sandstone face of Mt. Garfield and the sprawling Book Cliffs of Mesa County, there lies a place of desolate solitude called the Little Book Cliffs Wild Horse Range. Although it is certainly lacking in human dwellers, the dry and dusty landscape is home to a band of wild horses who have been roaming freely since the beginnings of Mesa County’s known history. According to an article written by David Wheeler from the Journal of the Western Slope:

“In 1881, when the northern Utes were forces out of western Colorado, it is probable that some of their horses were left behind in the far country north of Grand Junction, their blood blending with that of other horses introduced at a later time and adding to the complexity of heritage in today’s Little Book Cliff’s wild horse herd.”

Although majestic in appearance, the wild horses have not always been a beloved element of the Mesa County range. The influx of wild horse populations meant more and more farmland grasses were grazed upon. This wear and tear of the land began to upset local cattle farmers, and they felt strongly that wild horse populations should be lowered to protect their livestock. In the early 1900’s, government authorization was given to round up and kill wild horses, including those on the Mesa County range. Horses were seen as “pests,” and killed by cattlemen through any means necessary. Some were shot, while others were poisoned at their watering holes. Eventually the government starting using helicopters with blaring sirens to chase herds and run them into exhaustion for ease of capture.

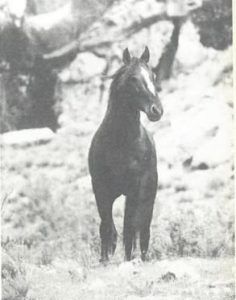

A stallion named “Big Red” in the Little Book Cliff Wild Horse Range. Photo taken by Marty Felix, sourced from the “Journal of the Western Slope: Volume 13, Numbers 1 & 2.”

Not all of America found the wild horses to be a nuisance. Many cowboys of early Mesa County days utilized the horses by rounding them up and taming them to help with cattle drives, transportation, and daily tasks. James Franklin was a cowboy of the great American West, and interviewee of the Mesa County Oral History Project. In 1906 James was 17 years old, and that’s when he completed his first wild horse round up. His job as a cowboy was to collect the horses and “break them,” so they would be suitable to ride. The top working wage around these times was about $30-$35 dollars a month, but strong cowboys were valuable. James was paid about $40 per month because well-trained horses were such a vital commodity for cattle outfits to successfully operate.

Morgan Goss was another cowboy and Mesa County Oral History Project interviewee who had a love for wild horses. He was only thirteen years old when he was given his first wild horse and told to break it:

“Yes, I rode horses ever since I was knee-high to a grasshopper…I’ve ridden everything from a pig to a (laughter) wild horse and wild cows, and wild bulls.” – Morgan Goss

Nowadays, The Little Book Cliffs Wild Horse Range is 36,113 acres and home to around 190 wild horses. The range was established by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) in 1974, and is one of only three wild horse areas in the U.S. set aside to specifically to protect the wild horses. It is presently well-maintained by a group of horse aficionados named The Friends of the Mustangs. Formed in 1982, this group works hard with the BLM to protect the horses, clean their watering holes, put them up for adoption to good homes, and keep population numbers reasonable through the usage of PZP birth control shots.

If you’d like to explore the Little Book Cliffs Wild Horse range and attempt to view these symbols of freedom, here is a hiking trail description. Also, for anyone wanting further interest on the subject, the following books explain the history, plight, successes, and lives of these beautiful wild creatures:

This article would be more complete if it included a link to Dave Wheeler’s Book: THE FAR COUNTRY= , ~ · W1LD HORSES, PUBL1C LANDS, AND THE LITTLE BOOKCLIFFS OF COLORADO

Here is the link:

https://spl.cde.state.co.us/artemis/umcserials/umc319internet/umc319v13n1-21998internet.pdf

Hi Flip, thank you for reading the library blog and for sharing this recommendation! I’ll connect the link you provided to Dave Wheeler’s article so reader’s will have better access to it in its entirety. With appreciation, Michele