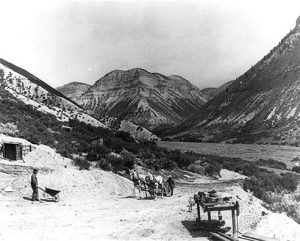

Hauling oil shale by horseback by Parachute Creek. [Image Credit: Museums of Western Colorado]

Our first big oil shale boom came in the years following World War I, spurred by federal encouragement to expand the nation’s petroleum reserves. This excitement attracted the attention of some of Colorado’s richest men, including Karl C. Schuyler of Colorado Springs. Schuyler was a politician and lawyer who, after an unsuccessful bid for a U.S. Senate seat in 1920, decided to finance a shale mining operation in Wheeler Gulch, about five miles north of Parachute (Known as Grand Valley at the time) along with his business partner Jimmy Doyle.

The Schuyler-Doyle Shale Company went off to a bad start. About a week before the operation was supposed to start, a labor dispute caused the mine’s workers to walk out, requiring Schuyler to bring in a new crew from Salida. Schuyler cheaply set up a tramcar to lift workers up and down the steep 2,000 foot incline, intended to be a temporary solution before a permanent car could be installed. What could go wrong?

On Saturday, July 30, 1921, something went terribly wrong. At 5 p.m., after completing their first day on the job, twelve workers boarded the tram to descend the mountain. As it started down the slope, the cable fastening gave way, snapping the cable from its post and launching the men down the sharp 70% incline, scattering men and machinery as it flew. The car reportedly reached a speed of 100 miles per hour before it jumped the track and smashed to pieces at the base of the slope.

Mining operations were often set up near the top of steep, shale-rich mountains like these, depicted in a 1920s photo from Dean Studio in Grand Junction. [Image Credit: Museums of Western Colorado]

Verifying the identities of the victims proved difficult, in large part due to the poor condition of their remains, the fact that they had no local connections, and the lack of consistency and rigor in newspaper accounts. The best source, while still flawed, comes from the Colorado Mine Accident Index, courtesy of the Colorado School of Mines, which records the list of names that the Schuyler-Doyle Shale Company was required to turn over after the incident. We have tried to include as much information as is known about each victim.

The list of victims includes:

- James E. Botts, De Beque, CO. He was survived by his wife and two children.

- C. E. Engel, possibly Elmer C. Engel, unknown address

- Lewis Fallice, also reported as Luigi Fellico and Louis Felice, age 22, Salida, CO.

- George Hines, accurately spelled as George Heins, age 30, Glenwood Springs, CO. Heins had a family he was supporting in Germany and was buried in Rosebud Cemetery in Glenwood.

- A. J. Lowe, Denver, CO. Buried in Rose Hill Cemetery in Rifle, CO.

- Mark Reba, also reported as Mark Reber, age 34, Salida, CO. He was survived by a sister in Salida, Mrs. George Blatnick.

- Frank Wolter, buried as Frank Walter in Rose Hill Cemetery in Rifle, CO. Age 17 or 18, unknown address.

Survivors were taken to St. Mary’s Hospital in Grand Junction, and included Nick Vasso (Glenwood Springs), Ray G. Lucas (Fairbury, NE), and James C. Ryan (unknown address), each of whom suffered from serious lacerations, broken bones, and internal injuries. Miraculously, three workers, including an unidentified 17-year-old, survived with only minimal scrapes and bruises. (The Daily Sentinel, August 1, 1928)

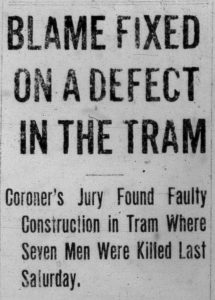

It did not take long for the coroner’s jury to reach a verdict. It is not clear if any legal proceedings followed. [The Daily Sentinel, August 3, 1921]

If nothing else, fate is full of fascinating coincidences. In 1932, Schuyler achieved his dream of becoming a U.S. Senator — a position he held for all of ninety days before he lost the special election, earning him the distinct honor of having one of the shortest Senate terms in U.S. history. In a bizarre repeat of the previous decade’s Senate loss followed by tragedy involving a runaway car, Schuyler visited New York City after losing his seat and, as fate would have it, proceeded to get hit by a runaway car. Two weeks later, Schuyler succumbed to his injuries.

As for the first oil shale boom, local shale companies suffered from the negative publicity from the incident in Wheeler Gulch, but the real death knell came with the discovery of cheap, fabulously rich deposits of crude oil in Texas later that decade. Oil shale simply couldn’t compete, and by the time the Great Depression rolled in, it had truly gone bust before it had really even got started. Local landholders and prospectors would have to bide their time, waiting for the next boom.

For more information on the local history of oil shale, I encourage you to check out Andrew Gulliford’s incredible Boomtown Blues: Colorado Oil Shale 1885-1985, and Armand de Beque’s lecture on the subject available through the Mesa County Oral History Project.

Images courtesy of the Museums of Western Colorado.

Images courtesy of the Museums of Western Colorado.

Well written nuanced. Thank you.