On certain quiet evenings, late into the night, it is said that you can hear an eerie whistle noise on the old narrow-gauge railway tracks between Grand Junction and Gunnison. The track begins to rumble, the air turns a sickly color that fills you with dread as the whistle squeals louder and louder until it twists into a ghastly scream. You close your eyes tight as the shrill screeching of wheels gnaw at your head. Suddenly, you hear a terrible crash among screams and the gnashing of metal. You open your eyes, trembling in fear, but there’s nothing there.

You decide to stop taking night hikes through the mountains.

There’s something special about the folk horror of the West. Whether it’s tales of cannibals living in the hills, disturbing cowboy murders, or mysterious ghost trains, they all contribute to the unique texture of the frontier. These are the stories that old cowboys would tell around the fire, where the line between fact and urban legend blur. In the case of the Dread 107, a train engine claimed to have killed up to 50 of its passengers and crew, it is not always clear where the truth ends and the myth begins.

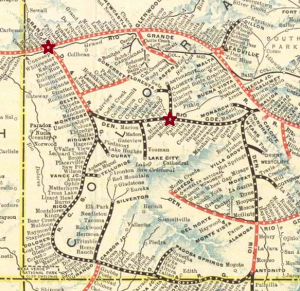

Map of the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad c. 1914 centered on Western Colorado. The red lines indicate standard gauge rails while the black lines show narrow gauge rails. Red stars have been added to mark Grand Junction and Gunnison. Click here to see an expanded version of this map. [Public Domain]

107’s first unlucky trip occurred on May 24, 1883, when the engine attempted to cross a bridge over the Gunnison River above the mouth of Roubedeau Creek. In the pitch of night, the engineer, William Duncan, failed to notice that the bridge had been overcome by the dashing waters of a flood. The bridge, unable to support the additional weight of the engine, collapsed as the train crossed over. The engine, baggage, and mail car were swept through the gap and submerged into the river. William Duncan and his fireman, Allen Emory, were immediately killed, though miraculously, none of the passengers suffered any injury.

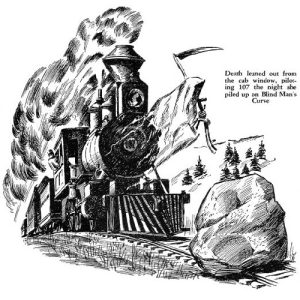

Illustration depicting the moments before the Dread 107 collided with a boulder, killing its engineer Edwin Godfrey. It reads: “Death leaned out from the cab window, piloting 107 the night she piled up on Blind Man’s Curve.” [Railroad Magazine, April 1949]

Those are the only deaths that can be corroborated with absolute certainty. Seriously. While three deaths in two back-to-back crashes is an unusual coincidence, it does not make for a particularly frightening story, nor does it come close to topping any lists of deadliest train accidents. Later tellings state that Sam Caldwell and several passengers were killed in the October crash, but no contemporaneous accounts include those deaths.

Most later accounts include the death of engineer Arthur Bratt, who was killed in the Black Canyon in April 1884 after an avalanche derailed his engine, but none of the archived news articles about his death seem to mention the engine number, so it’s entirely possible it was a different train. You would think that news organizations would find it interesting to mention if it were the same engine – they did for the crash involving Edwin Godfrey – but if we wanted to be uncharitable to the local press of the 1880s, we can say that maybe they just didn’t think to mention it.

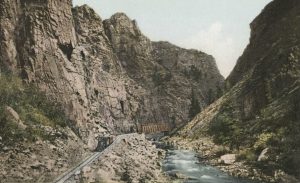

Postcard depicting a stretch of railway along the Black Canyon of the Gunnison, c. ~1898. [Public Domain]

It’s said that the engine was transferred to the Salt Lake City to Ogden rail at this time, since no Colorado crew would run it any longer. The engineer, a man named “Mad ‘Ole” Gleason, was apparently a bit of a daredevil, and had been railroading for over 15 years without a scratch. The train suffered a few minor accidents, including a rear-end collision with another train in which no one was hurt and a derailment that killed a vagrant who snuck onto one of the cars. Within six months of stepping foot in the Dread 107, ‘Ole Gleason crashed head-on into a cattle train, and was killed along with 4 other crewmen. 107 was so battered up by this point that she was transferred to freight service after being fixed up again.

Baldwin 8-18c class narrow gauge locomotive, similar in make to the Dread 107. [, 1885]

The most astonishing incident occurred on her sixth anniversary, with engineer Tom Flynn and his brother as fireman. As the engine departed from Ogden, Tom opened the valve controlling the throttle, lurching the engine forward at dangerous speeds. It proceeded at blistering pace for the next twelve miles, when she rolled over an embankment and crashed. Fireman Flynn was found unconscious several miles away from the crash, delirious, and told of a mad tussle over the controls with his brother before he was thrown from the cabin. He died of internal injuries the next day. Tom was found pinned beneath the engine, babbling incoherently, before eventually bleeding out. Apparently, he had grown mad while staring at the list of names carved into the cabin.

After this incident she was once again transferred, this time to Alamosa, on the other side of the Rocky Mountains. As the story goes, the offensive death roll was removed from the cabin during remodeling, along with a change in number to #100 to eliminate any superstition with the number 107. During this time there was another rollover during which Engineer Peters was scalded to death by the boiler. When the train arrived back in Alamosa, the number had been mysteriously changed back to #107.

The last recorded story involved engineer Frank Murphy, who ran a heavy gravel train from Mears Junction to Alamosa, downgrade all the way. Six miles down, Murphy realized he had lost control of the train. He shut off the steam, applied the air brakes, and whistled the alarm, but to no avail. The runaway train collided with a mixed train down the pass, and the wreck of both trains caught fire. No one lived to tell the tale. After that, the Dread 107 never made another run.

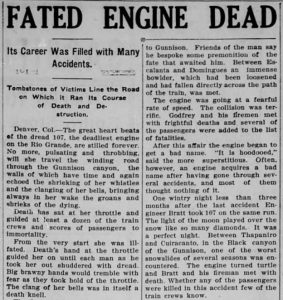

Dread 107 wasn’t merely dismantled, but physically died. The article goes onto describe the “pulsating and throbbing” of her beating heart, now forever stilled. It almost comes across as an obituary. [The Longmont Call, July 24, 1909]

Here’s the thing: official Denver & Rio Grande records show that #107 was scrapped in August 1898. Additionally, the same records show that #100 was scrapped in 1908, one year before the death of the Dread 107 was reported in the news. Less sensational accounts of the #107 also seem to confirm this earlier date. In a 1902 edition of Munsey’s Magazine, purported to be the first written account of the Dread 107, it was claimed that the engine killed nine engineers over twenty months and was scrapped when she was still new. Nevermind that even the most outlandish retellings can only name the seven engineers that we’ve discussed over nearly twenty years, because Munsey’s Magazine doesn’t name any of the victims. If it’s true that the engine was scrapped in 1898, then why all the sudden attention in 1909?

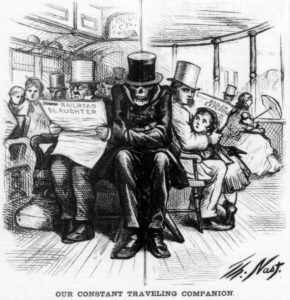

“Our Constant Traveling Companion” by Thomas Nast, c. 1871. The frequency of railway accidents in the 19th century produced deep anxieties surrounding the safety of rail travel, likely contributing to exaggerated stories about cursed trains. [Harper’s Weekly, September 16, 1871]

This was a time when train accidents were plentiful, accurate record-keeping was a rarity, and superstition prevailed. People told stories around the fire to entertain and frighten, and there was certainly no shortage of unscrupulous writers willing to exaggerate or invent details to sell papers and magazines.

But hey, it makes a good story. There are certainly enough discrepancies and unanswered questions for you to come to your own conclusions. Perhaps we’ll never have the full picture of what went down on the cursed Dread 107, but we can at least enjoy the richness it adds to the folklore of the West.

_________________

Have you ever heard of the Dread 107? Do you have any railroad knowledge to share? Have you found any primary sources that help to solve some of these ongoing mysteries? Please let us know in the comments!

Thank you for reading!