Deserted, remote, forgotten. With over 1,500 named ghost towns, few states possess more abandoned settlements than Colorado. The promise of prosperity brought thousands into these settlements, only to be left behind when fortunes dried up.

The vast majority of ghost towns in Colorado were mining settlements, founded to extract or process raw material from Colorado’s rich mountains. A cycle of boom and bust brought settlers in and spit them out when resources dried up.

This is an introduction to just a small handful of ghost towns in western Colorado, some of which were chosen due to their notability, whereas others were chosen for having interesting names. Many of these can still be visited, although there’s not always much left to see.

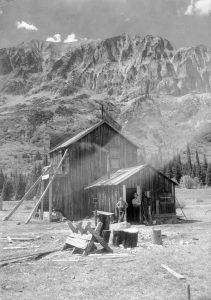

Men outside of the town hall and saloon in Gothic, c. 1920, with Gothic Mountain in the background. [Denver Public Library]

Gothic (Gunnison County)

An appropriate name for a ghost town if ever there was one. Gothic is located in Gunnison County in the West Elk Mountains, near Crested Butte. It was founded after deposits of silver were discovered in September 1878 by Truman Blancett. As the story goes, he had only told two people about his discovery, but when he returned in the spring, there were already two-hundred prospectors who had set up camp. (Robert Brown, Jeep Trails to Colorado Ghost Towns, 103) This just happened to occur at the same time that silver was discovered in Leadville, prompting a massive rush of prospectors hoping to strike it rich. This silver rush made Leadville into the second most populated town in Colorado, and helped shape Gothic into its own bustling community. By 1881, the town had over 1,000 people.

Gothic was named after the nearby Gothic Mountain, prominent a 12,631 foot summit with steep cliffs and sharp pinnacles said to resemble gothic architecture. While it had a strong start, the town quickly depopulated once the silver mines were depleted. Only one resident, Garwood Judd, remained to look after the town, a solemn duty he performed for over twenty years until his death in 1930. Today, the ghost town has found new life as the site of the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory, a field station used for studying high-altitude ecology, climate change, and pollination science.

Climax (Lake County)

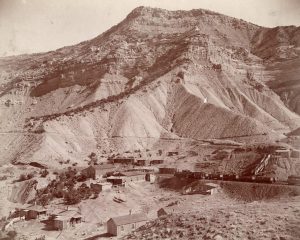

The crushing plant, water towers, and tramway in Climax. [Denver Public Library]

Climax was named for — what else? — its location at the summit of Fremont Pass on the Continental Divide. The Climax lode — please stop laughing — was first discovered by Charles Senter, a miner who had set up camp during the Leadville boom. It was originally mistaken for a form of lead ore called galena, which often contains small but profitable deposits of silver. In this case, there was no silver to be found, so the Climax lode was forgotten about. The Colorado School of Mines correctly identified the ore as molybdenum in 1900, but there was little demand until World War I, when there was a need for high-quality steel. The mine, operated by the Climax Molybdenum Company, grew to epic proportions, eventually leading to the demolition of the original ghost town to accommodate its expansion into a pit mine. The mine still operates today, though not without its own long periods of inactivity between market crashes, but the original ghost town is forever gone.

Carpenter (Mesa County)

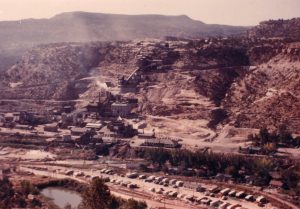

Carpenter at the foot of the Book Cliffs. [Image courtesy of the Museums of Western Colorado]

The main attraction was a natural spring located above the Book Cliff mine, which he marketed as having medicinal properties. While there were some vague claims that consuming the water could cure disease, it is generally agreed that, if nothing else, it was an “extraordinary laxative.” (Lyndon J. Lampert and Robert W. McLeod, Little Book Cliff Railway, 41.) Carpenter renamed the town to Poland Springs and began bottling the product. It is certainly no coincidence that he chose this name after a business trip to New England, where Poland Springs remains a well-known resort with a popular bottled water label found all throughout the east coast. Mesa County newspapers almost never referred to it as Poland Springs, however, but instead misspelled it as Polen, Pollen, or Polan Springs.

Plans for promoting the town as a resort fell apart when Carpenter went bankrupt following the Panic of 1893, an economic depression caused in large part by the collapse of the silver industry. Yes, even in this story, it all comes back to silver. Before long, Carpenter was forced to sell, and he proceeded to move on to prospect in the gold rushes in Alaska and the Yukon Territory. The purchase was financed by Princeton University, but they had no interest in developing the mines any further. In 1924, a fire caused the mines to be sealed for good. There’s little left of the town of Carpenter today, but it still makes for a fascinating hike for anyone interested.

Our very own Ike and Noel have written about Carpenter before, so be sure to check out their work for more information!

- Finding The Little Book Cliff Railway

- A Ghost Town With an Alias

- Local History Thursday: Bookcliff Avenue and the Little Book Cliff Railway

Uravan (Montrose County)

Uravan, c. October 1952. [Image courtesy of the Museums of Western Colorado]

Uranium production grew exponentially in the Cold War. By the 1960s, the U.S. and Soviet Union had stockpiled enough nuclear weapons to render large portions of the world uninhabitable. Uravan’s fate was tied closely to the atomic age, and when production waned in the 1970s, the community fell into decline. In 1985, the town was declared a public health hazard due to high radioactivity, and the 800 remaining residents were forced to relocate. Today, the town is a Superfund site managed by the Colorado Department of Public Health & Environment and the Environmental Protection Agency. Visitors are strictly prohibited, but there’s not much to see anyways beyond the interpretive sign marking the edge of the site, since remediation involved removing all buildings and burying what remained.

View of the Tomboy Mine and Mill in the Savage Basin. [Denver Public Library]

Tomboy (San Miguel County)

I’ll admit it, I was disappointed to learn the truth behind this ghost town’s name. With a name like Tomboy, I expected an epic tale of a wild and rugged female pioneer with a bold personality who made a name for herself through her exceptional sharpshooting and riding skills — someone like Annie Oakley or Calamity Jane. Unfortunately, the reality is much less exciting. Tomboy is named after its founder, Otis “Tomboy” Thomas, who established a mine in the Savage Basin two miles east of Telluride in 1880. In turn, the Savage Basin was named for its steep, dramatic geography formed by glacial erosion in the San Juans. At 11,500 feet in elevation, Tomboy actually beats Climax as the highest elevation ghost town in the United States (Tomboy didn’t have a post office, however, so Climax still wins on that technicality).

Despite its rugged environment, Tomboy had a surprising number of amenities for a mining community in the late nineteenth century. It possessed a school, a store, worker housing, stables, and even a YMCA and tennis courts. The Tomboy Mine produced gold in ore in 1894, and grew profitable enough that the mine was purchased by the Rothschilds family for a substantial $2 million. Like the other mining communities discussed here, the population declined as the source of wealth declined, until eventually the mine was shut down in 1928.

____________________________

Many of these abandoned communities can still be visited, though there’s not always much left to see. If you do want to visit any of them, please be sure to plan ahead and do lots of research before going ahead. You do not want to be stuck in a remote, rugged location without a decent off-roading vehicle that can handle the unmaintained roads. It’s best to avoid visiting some of these high-elevation places in the winter as well, where road conditions are at their worst. Take it from my personal experience, there is nothing scarier than taking hairpin turns on an icy road where one mistake can mean falling thousands of feet to your doom. Use your best judgment, nothing described here is worth risking your life over.

I would also like to caution against entering any abandoned structures and especially against entering any abandoned mines. In addition to the danger posed by cave-ins from unstable construction, mines are often filled with deadly gasses, explosives, and numerous other hazards. People can and have died exploring many of the abandoned mines discussed here. Protect your life: stay out, stay alive.

Lastly, if you find any artifacts or historic items, please leave them where you found them. It is against state and federal law to disturb or remove any historic materials. Don’t be a looter! Please protect our state’s history so that future generations may learn and appreciate it.

Thank you to the Friends of Mesa County Libraries for supporting Local History blogs like these.

Good story. Interesting facts.