Living in Grand Junction, founded in 1882, can skew your perception of just how far back much of Colorado’s history goes. Comparatively speaking, the towns and cities on the Western Slope are much younger than the towns and cities located elsewhere in the state, in large part because this land was reserved by treaty for “the absolute and undisturbed use and occupation” of Ute Indians for much of the early history of the state — until it wasn’t. 142 years may seem like a long time, but it doesn’t take much to identify places that are much, much older in this state.

Of course, actually identifying the oldest towns and communities in Colorado is much easier said than done. In the interest of avoiding arguments over what counts as a town, we will take a broad approach that will include any sites or locations with permanent dwellings and some form of sedentary economic activity, such as farming, mining, or trapping. This is not a complete list by any means, but simply a fun tour through a handful of old places.

1858 – Denver and Boulder

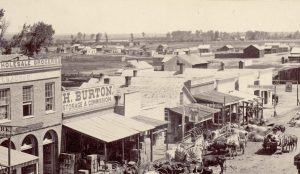

Blake St. in downtown Denver, c. 1860. [Denver Public Library Special Collections, ]

Denver (or at the time, Denver City) was named after the Territorial Governor of Kansas, James W. Denver, with the intention that he would be so honored that he would name Denver as the county seat of Arapahoe County, unaware that he had resigned about a month earlier. James Denver did not visit the city until 1875, and he was rather disappointed by the cold welcome he received, writing “I naturally received the impression there were not many people in Denver City who cared much about me.”

Boulder’s name is less interesting. It is named after Boulder Creek, which as you might imagine, was named because it has boulders in it. In fall 1858, gold prospectors were camping near the mouth of Boulder Creek when they were confronted by Chief Niwot of the Arapaho. Niwot asked them to leave, but the prospectors told him they had only come for the winter and promised to leave in the spring. Hoping to avoid conflict with the white settlers, Niwot relented. The prospectors then found gold, and were unwilling to leave. Soon after, the Arapaho and Cheyenne tribes were forced to negotiate a new treaty surrendering the Front Range to white settlers. Niwot was later killed in the Sand Creek Massacre.

1851 & 1849 – San Luis and Garcia

Sangre de Cristo Catholic Church in San Luis, built 1886. [Photo taken 1959, Denver Public Library Digital Collections, Z-419]

Some settlers had tried to establish villages in the San Luis Valley before, but they were run off by the Caputa band of the Southern Utes, who fiercely defended their territory. The United States government signed a treaty with the Utes in 1849 to enforce peace with American citizens and to allow the government to establish forts and agencies in their territories. Thus, the New Mexican Hispanos (who were now American citizens) could freely establish settlements in the San Luis Valley. That makes the Hispano culture of San Luis and Garcia as American as baseball, which first developed a standardized ruleset in that same decade.

As for their names, the church of San Luis was dedicated on June 21, 1851, which is celebrated by the Catholic Church as the Feast of Saint Louis — it is very common for Spanish towns to be named after their churches. Garcia was originally named La Plaza de los Manzanares, named after the two brothers who founded it, Manuel and Pedro Manzanares. It was later renamed to Garcia by an additional pair of brothers, José Guillermo and Agapito García, who petitioned for a post office to be established in their name in 1915. A lack of historical documentation makes the debate over which town came first somewhat contentious. The Colorado State government recognizes San Luis as the oldest continuously occupied town, but that’s mainly because it was officially incorporated in 1852, whereas Garcia was never formally incorporated. Without incorporation, Garcia may not meet the technical definition of a town, but it is probably more deserving of the title.

1807-1847 – The Many Forts in Pre-Territorial Colorado

Most people would agree that forts and trading posts don’t count as permanent settlements, especially because the majority of them were quickly abandoned and have few, if any, remaining structures. And yet, they remain important entries in the early settlement of the state, with the trails and locations serving as the foundations for several towns and cities to follow.

Reconstruction of Pike’s Stockade, erected in 1952. The original structure has long been destroyed. [Photo taken 2012, Wikimedia Commons]

In anticipation of further American encroachment into their territory, the Spanish built a fort of their own in the San Luis Valley in 1819. Fort Sangre de Cristo, also known simply as the Spanish Fort, was constructed in the Sangre de Cristo pass across the range of mountains bearing the same name. Sangre de Cristo is Spanish for “blood of Christ,” and was possibly named for the red hues that reflect off of the cliffs during sunrise and sunset, particularly when capped with snow. The fort was abandoned in 1821, just a few short months before Mexican Independence.

Another early fort was Fort Uncompahgre, built 1828 by fur trader Antoine Robidoux as a trading post at the confluence of the Gunnison and Uncompahgre Rivers. Fort Uncompahgre’s location was chosen due to it being a favorable meeting location for the Utes. In addition to being a trading post for pelts and goods, it was also, illicitly, a place where Native slaves were sold to perform domestic and agricultural labor in New Mexico, despite Mexico banning the practice in 1830. Their relationship deteriorated as Mexican settlers expanded into the San Luis Valley, and turned into all-out war in September 1844 when a Ute chief was killed in a delegation to the Governor’s mansion in Sante Fe. Enraged Utes razed Mexican settlements and trading posts from Santa Fe to Fort Uncompahgre — where three Mexican employees were killed, likely from guns supplied to the Utes from that very fort. The fort was abandoned soon after.

Oh, and the word Uncompahgre comes from the Ute language. Depending on the translation, it can either mean “warm flowing water,” “red water spring,” or “dirty water.” It probably refers to the red silt and sediment that flows in the rivers, streams, and springs in Western Colorado. In that sense, it actually shares a common origin with the word Colorado, which means “colored red” and originally referred to the Colorado River.

~300 BCE to ~1300 CE – Basketmakers and Ancestral Puebloans

View of the Cliff Palace, c. 1908. Since then, much of the debris has been cleared and several of the buildings have been restored. [Denver Public Library Special Collections, ]

Older still are the villages and sites located on the tops of mesas, where the Ancestral Puebloans lived before settling down in the more defensible cliff dwellings. The Far View Community, located on Chapin Mesa, was once an extensive farming community with nearly fifty villages located in a half square mile area. The earliest structures can be dated to about 800 CE, but continued to be occupied until 1300 when the other Mesa Verde sites were abandoned. This was among the most densely populated communities in the Mesa Verde area.

Of course, the Ancestral Puebloans had ancestors of their own. Known to archaeologists as the Basketmaker culture, these peoples were the transition between the hunter-gatherers of the Archaic period and the agricultural communities of the Ancestral Puebloans. The culture existed between the years 1500 BCE to about 750 CE, when archaeologists delineate a transition to the Ancestral Puebloans. The transition from hunter-gathering to sedentary farming necessitated the Basketmakers to begin permanent settlements. The typical home consisted of a shallow pit around a central hearth and a thatched roof with a hole for smoke to escape. Nearby pits would often serve as storage for surplus food.

The oldest known Basketmaker pithouse in Colorado is located on the southern hills of Sleeping Ute Mountain, around 15 miles west of Mesa Verde in the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe Reservation, called site 5MT10525. This site is dated between 405-75 BCE, and was likely occupied in some form before the Basketmaker era. With some generous math, this site would have been about as ancient to the Ancestral Puebloans of Mesa Verde as the Ancestral Puebloans are to us today.

____________________________

If there’s one lesson that can be learned from all of this, it’s that there’s always something older. Even the Basketmakers would have recognized that they had ancestors with deep connections to the land. It’s important to adjust your scales and look beyond the recent past to understand the full complexity of human development within our state’s borders. Those borders may just seem more and more arbitrary the further back you go.

Again, this is by no means a complete list. There are plenty of other towns, forts, and pueblos that are worthy of discussion. Can you think of any we missed? Want to respectfully debate what should count and what shouldn’t? Be sure to leave a comment!

If you are reading this when it comes out, it is currently Native American Heritage Month. We would like to expression recognition for both the significant history of Native Americans in this state as well as the displacement and loss of land that came with the settlement of many of these locations. The choice to center this discussion around permanent settlements in the form of towns and cities excludes many indigenous nations with equally long histories who simply followed alternative forms of community.

Thank you to the Friends of Mesa County Libraries for supporting Local History blogs like these.

Interesting

This was a very interesting read! I’m interested in learning about the “town” of Tunnel, what I believe is the chimney that remains at mile marker 51 on I-70.

Thank you for sharing, Judy! I can’t say I’m too familiar with any abandoned towns near that spot. Might make for an interesting deeper dive!

Kristen,

Very informative and enjoyable brief account. Yes, our initial interactions with First Nation peoples was not a good one, and continues to be at best, problematic. I really like your longer posts, keep it up. Thank you.

Thank you kindly! I’m happy to oblige.