Read part one, “Temperance and the Colorado Frontier.”

Content Warning: This story describes racist attitudes towards Native Americans during the 19th Century and includes some graphic depictions of violence. Reader discretion is advised.

As Nathan Meeker departed from Greeley to the Indian Agency on the White River, he reflected on his past experiences in self-sufficient agriculture. His experiences in the Trumbull Phalanx Colony and Hiram community in Ohio early in his life left him bitter and poor. His colony in Greeley could only be considered self-sufficient if he ignored the mountain of debt he accrued to keep it afloat – the very debt which motivated him to seek appointment as Indian Agent. Past failures did little to shake Meeker’s confidence in himself, however. He was Father Meeker – temperate, moral, industrious, and intelligent – and he would be the one to guide the Utes to proper civilization.

This is part two in our history of Nathan Meeker, temperance, and town building on the Colorado frontier. Part one focuses on Nathan Meeker, William Pabor, and the temperance colonies they founded on the Front Range (Greeley, in particular). Some of that context will be relevant for part two, so check it out if you haven’t yet. This segment will be focused on Meeker’s appointment as Indian Agent to the White River Indian Agency, the violent incident that ended with his death and the removal of the White River and Uncompaghre Utes from Colorado, and the rapid settlement of Western Colorado in the aftermath of Ute removal.

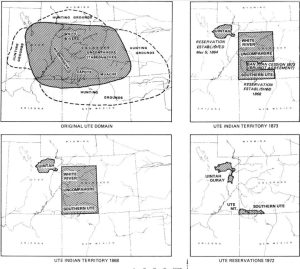

Map showcasing the stages of Ute removal. [Bureau of Land Management, from Robert W. Delaney, The Southern Ute People]

For Frederick W. Pitkin, an attorney who moved to Colorado in 1874, Ute removal was personal. After the 1873 agreement was signed, he made a small fortune through investing in silver mines in the San Juans. He leveraged his connections with the territory’s mining interests to eventually become the state’s first elected governor in 1879. His platform explicitly called for the termination of the reservation, “This tract contains nearly one-third of the arable land of Colorado, and no portion of the state is better adapted for agricultural and grazing purposes […] there is reason to believe that it contains great mineral wealth. […] If this reservation could be extinguished, and the land thrown open to settlers, it will furnish homes to thousands of the people of the state who desire homes.” (Quoted in Robert Emmitt, The Last War Trail, 21-22) Pitkin wanted the Utes gone, no matter what it took.

Senator Henry Teller largely agreed that the reservation should be opened to white settlement, but preferred an approach that would allow the Utes to be assimilated, rather than exterminated. The Utes would be required to abandon their traditional ways of life and adopt white American customs and social organization. Meeker convinced Teller to recommend him for appointment as Indian Agent, in large part due to a shared belief that the Indians could be civilized by adopting agriculture, a Christian education, and of course, temperance.

The White River Agency was one of two agencies established in the reservation by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the other being located on the Los Piños River (later moved to the Uncompahgre Valley). These agencies had the primary purpose of distributing rations and annuities to the Utes, and a secondary purpose to “insure the civilization” of the bands by forcing them to adopt agriculture and a Christian education. The annuities were another contentious issue. Due to the remoteness of the agencies and dereliction from the federal government, only about half of the promised flour, clothing, blankets, tents, and tools were provided for. The agencies could not be relied on to provide basic necessities, so the Utes would frequently leave the reservation to hunt and trade. (The Utes Must Go, p. 98)

Meeker hoped to change that. His first move was to move the agency downriver to Powell Park, a fertile valley more suited for agriculture, which the Utes used primarily for grazing horses (The Utes Must Go, p. 99). Horses were incredibly important to the Utes, who used them to travel long distances to hunting grounds, connect with traders, and also served to indicate status. Chief Douglas, the eldest sub-chief at the White River agency, derived his status from his possession of 100 prized horses.

Chief Quinkent, also known as Chief Douglas or Douglass. [Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper]

Meeker had little success convincing the Utes to stay on the reservation and farm. The Utes found his lectures on the merits of Christianity and agriculture to be long-winded and self-righteous. They had been self-sufficient for centuries before the arrival of Spanish and American settlers – why should they change now to a system of sustenance that seemed so unreliable? The “civilization” promoted by Meeker and the government had only brought pain and misery to Indians across the continent. If the Utes desired anything from this “civilization,” it was their guns, ammunition, and alcohol – the very same things that Meeker wanted off the reservation.

While the Utes were always peaceful and polite to Meeker, they had little respect for his authority. His attempts to assert control went ignored. Meeker eventually concluded that in order to encourage the Utes to farm, he would have to dismantle their horse culture. “Only those [few] young men who have no horses will work,” he complained in letters to the Bureau of Indian Affairs, “this horse business is a powerful obstacle to progress.” (The Utes Must Go, p. 106-107)

He devised a scheme to plow fifty acres of prime horse pasture in Powell Park in order to cut down on the number of horses. Chiefs Douglas, Johnson, and Jack confronted Meeker, insisting he plow elsewhere, but Meeker refused, threatening to have them arrested and removed from “government land” if they interfered. Jack sternly reminded Meeker that the reservation belonged by treaty to the Utes alone. Unabated, the plowing proceeded as planned. The next day, a warning shot from an unidentified Ute whizzed by the agency plowman’s head. The plowing was temporarily stopped, but tensions had risen higher than ever. (The Utes Must Go, p. 114-116)

Home of Chief Johnson on the Agency Farm. [Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper]

Growing increasingly frustrated, Meeker relied on what little leverage he had at his disposal. He began to withhold rations, continued to plow land used for grazing horses, and sharpened his threats to arrest any disobedient Utes. Days after the initial confrontation, Chief Johnson once again approached Meeker to demand an end to the plowing. They exchanged a few tense words before Johnson laid his hands on the agent. According to Johnson, he had only grabbed him by the shoulder and insisted he leave, without striking him or anything else. Meeker, clearly rattled, charged Johnson with dragging him out of his office and throwing him on the ground, injuring his shoulder. Even Meeker’s stubbornness had its limits. He swallowed his pride and sent a telegram to request the army send a few soldiers for his protection.

Rather than sending a few soldiers, Major Thomas Thornburgh advanced from Fort Steele in Wyoming with 191 men in tow. Upon hearing this, Meeker sent a message insisting that Thornburgh only send five men, fearing that the Utes would see this large movement of troops as a major escalation. Captain Jack also met with Thornburgh to inform him that the movement of soldiers onto the reservation would violate the Treaty of 1868. (The Utes Must Go, p. 132)

Thornburgh responded saying he would advance his troops to the boundary of the reservation, on Milk Creek, and then proceed to the agency with five men. This seemed to satisfy both Meeker and Captain Jack. Thornburgh, however, changed his plans last minute. His command instead would follow him onto the reservation, and from there they would set up camp nearby for support. Meeker assured Chief Douglas that the soldiers would not cross into the reservation. (The Utes Must Go, p. 139)

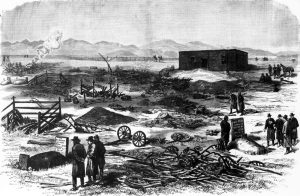

The death of Major Thomas Thornburgh at the Battle of Milk Creek. Captain Jack later claimed it was his bullet that killed Thornburgh. [Library of Congress]

Three hours after the battle began, a messenger arrived at the agency to confer with Douglas. Shortly after, the agency was stormed by twenty armed Utes. Ten employees were killed, nine of whom were Meeker’s cadres from Greeley, and the buildings were set ablaze. Five women and children were taken hostage, including Meeker’s wife and daughter. Days later, after the battle had ended, troops arrived at the agency to find Meeker laying outside of his office, shot through the head, with a logging chain wrapped around his neck, and a metal stake pounded into his throat and through the back of his skull. The message sent was clear: Father Meeker would tell no more lies (The Utes Must Go, p. 133-144).

Aftermath of the Meeker Incident, sketched by Lt. Charles McCauley. [Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper]

At first, it was suggested the Utes be moved to the Grand Valley in Western Colorado, but these plans changed once surveyors discovered the agricultural potential of the valley. (The Utes Must Go, p. 178) The Utes were instead moved to smaller reservations in Utah and Southern Colorado, opening up Western Colorado to white settlement. White settlers wasted no time building railroads and establishing communities in the opened territory. The small mountain town of Meeker was one of the first new settlements founded in this region, located a few miles upriver from the former White River Agency. However, unlike the other communities associated with Meeker, it was never a dry town.

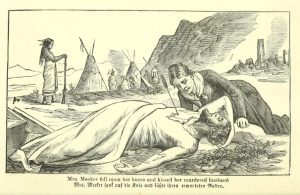

Many posthumous reports highlighted “Father” Meeker’s devout Christianity, which perhaps inspired the martyr-like imagery in this depiction of Mrs. Meeker lamenting the death of her husband. [The Ute Massacre!]

With the removal of the Utes, the last frontier in Colorado had been subdued. Pabor would go on to found the town of Fruita in 1884 in the territory now opened up to white settlement, modeled after the colonies he helped found in Greeley, Colorado Springs, and Fort Collins. “The pioneer system has had its day,” he wrote, noting the end of Colorado’s frontier days, “The colony system takes its place.”

Fruita, like the other communities Pabor was involved in, was established as a temperance town. It was advertised as a place where “society is good” and “moral sentiment […] prevails.” More notoriously, Fruita was also known as a sundown town – a town that practiced a form of segregation that prohibited non-whites from staying after sundown – until at least the 1930s. Their idea of a town where “moral sentiments prevailed” was one that rejected alcohol and other races equally.

Despite everything, the Ute people are still around today. Too often, Native Americans are only considered in the context of history, both as victims and as cultural relics, and not as living breathing people. The Utes still call this region home, not as relics of a bygone era, but as friends, neighbors, and community members. Today, efforts on mending the wounds of the past are focused on the Teller Institute, an off-reservation boarding school established in Grand Junction by Senator Henry Teller in the 1880s, meant to further assimilate Ute children by destroying their cultural ties and educating them in agriculture. Our history is unfortunately filled with many examples of cultural genocide, but by acknowledging the scars of the past, we can look forward towards building a brighter future.

_________________

One of the most fascinating things about studying history is learning how one event can lead to another in very unexpected ways. The temperance movement led to Nathan Meeker founding Greeley, which led to him becoming Indian Agent, which led to him getting killed, which led to Ute removal and the founding of the very city I am writing from. Of course, it would be an oversimplification to say that temperance caused Meeker’s death, but it’s interesting to see the chain of cause-and-effect in action. Like watching one domino fall after another, the picture only becomes clear when you take a step back.

For more information on the causes and effects of Ute removal, I highly recommend The Utes Must Go! by Peter Decker. He goes into exquisite detail about things I only touched on briefly, especially about the Battle of Milk Creek and the aftermath in Washington. I also recommend The Last War Trail by Robert Emmitt, which records the narrative history told by the Utes themselves and is based primarily on interviews with direct descendants of Utes at the White River Agency. The Colorado Historic Newspaper Collection provides another invaluable source for research on this topic.

Any thoughts or comments? Different perspectives or sources I didn’t include? Please let us know in the comments!

Thank you for reading.

Thank you to the Friends of Mesa County Libraries for supporting Local History Thursday.