Illness and infectious disease reigned in 19th century America. Without the modern antibiotics and vaccines to properly treat diseases like cholera, smallpox, and tuberculosis, a burgeoning health tourism industry emerged to provide comfort and care in locations that could meet people’s needs. With its clean mountain air, abundant natural springs, and sunny climate, Colorado became the major destination for the country’s sick and unwell. By 1900, approximately one-third of the state’s population had come to treat their tuberculosis, earning the state the nickname of “the World’s Sanatorium.” Colorado Springs, Manitou Springs, and Glenwood Springs all emerged as ideal spa destinations for travelers seeking better health due to their natural spring waters.

It’s no surprise then that for William Thomas Carpenter, a successful banker and coal magnate on the Western Slope, his largest aspirations lay not in the successful coal mines he possessed north of Grand Junction, but in the natural spring located in the Book Cliffs above the mines. In his loftiest ambitions, the mining town of Carpenter, if properly managed, could become a resort that not only rivaled the prominence of Glenwood and Manitou Springs, but could supplant Grand Junction as the major city on the Western Slope. Perhaps this was an unrealistic expectation for a small mining operation of no more than fifty people, located in a narrow canyon in the desert, where the only water is a spring with a flow of just 1 ½ gallons per minute. To Carpenter, such details were only minor shortcomings that could be resolved through shrewd planning.

It was a secondary priority compared to mining coal, to be sure, but it does play an important role in defining Carpenter’s vision for his building his town. The prevailing attitude among pioneer citizens in the Grand Valley was boosterism, or promoting the region to attract new citizens and business. As the preeminent banker and financier in the first decade of Grand Junction’s existence, Carpenter may well have done more than any other person to grow the town in its early days. If there was one person who could develop the Book Cliff Mines into a booming resort town, it was him.

In the summer of 1890, he built piping and constructed a tank to store the spring water at his mines and announced that he would construct a bathing pool for guests. He also began work on the Little Book Cliff Railway, a narrow gauge rail designed to transport coal from the mines and deliver tourists to the springs. Though it lacked the health accommodations of a sanatorium, the prospect of pure water at an attractive destination offered plenty of novelty for the pioneer residents of Grand Junction: “A picnic at the Book Cliffs! Who would have thought of such a thing five or six [years] ago?” heralded the Grand Junction Weekly News in July 1891, “One would have been laughed at for suggesting it.” (Lyndon J. Lampert and Robert W. McLeod, Little Book Cliff Railway, 36.)

Advertisement for Poland Springs Water. The Poland Springs in Maine, that is. [The Sun, December 9, 1894]

In June 1892, he constructed a pavilion for visitors and acquired a bottling apparatus for the mineral water. By this point, Carpenter’s “famous soda springs” had already earned a reputation as a powerful cure. “There are many who have used this water who claim they have been cured by its medicinal qualities simply by drinking it.” once reported the Grand Valley Star.

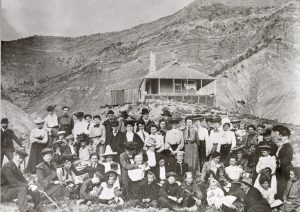

An excursion of young ladies who visited Poland Springs to pick wildflowers. [Image courtesy of the Museums of Western Colorado.]

Further boosting the reputation of Poland Springs and its mineral water was Dr. Edward F. Eldridge, a local surgeon, poet, and avid town booster who had moved to Grand Junction to alleviate his own health issues in 1890. In a letter to the editor of the Grand Valley Star, he published his own findings on the quality of the famous Poland Springs Mineral Water:

“Some three weeks ago I procured a bottle of water from the springs at the Book cliff mines, and have examined the same. I find it contains 48 grains of solids to the gallon, composed of the sulphate of magnesia, sulphate of soda, chloride of soda, chloride and sulphate of feri, besides traces of several other salts. It is entirely free from organic matter, slightly alkaline in reaction, and on the whole a very palatable table water. The carbonic acid gas which is added at the bottling works is a great advantage, as it renders it slightly acid, increasing its tonic effect, and makes it the equal of any as general table water.”

Many natural spring waters come naturally carbonated, but it was also common to add carbonic acid when bottling to emulate those natural sodas. On its health effects, he reported:

“The ‘Glauber’ and ‘Epsom’ salts which it contains are excellent hepatic and renal stimulants, and in the case of torpid liver or congested kidneys act very mildly and efficiently. For the same reasons they are indicated in all bilious tendencies or to aid in the recovery from those conditions. The iron is a natural tonic and invigorant, while the combined sulphur is a blood purifier of the first order. From the result of my personal observation of the use of these waters and the chemical examination of them I heartily recommend it to the public as equal to any as a general tablewater.

Yours very truly,

E. F. Eldridge, M. D.”

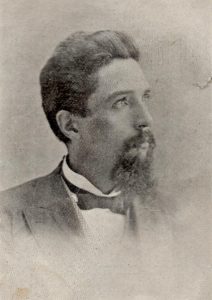

Edward F. Eldridge, M. D., was a prominent local physician who promoted Grand Junction in nationally-circulated essays as “the most perfect and natural sanitarium for the invalid with which this earth is blessed.” [Grand Junction as a Health Resort, courtesy of the Museums of Western Colorado]

Indeed, the presence of magnesium sulfate (Epsom salts) and sodium sulfate (Glauber’s salts) both serve to draw water into the intestines and are commonly used as laxatives. The “sulphate of feri,” refers to iron sulfate, a primary ingredient in over-the-counter iron supplements that is known to cause constipation and diarrhea. At 48 grains of solids to the gallon, or 822.72 parts per million, these dissolved solids are present in sizable concentrations.

Even if not a miracle cure, an “extraordinary laxative” may have been the perfect remedy for the most common ailment suffered by Americans in the 19th century: dyspepsia — a now-obsolete diagnosis used as a blanket term for indigestion, constipation, diarrhea, and any other gastrointestinal affliction.

Historian Gerald Carson once dubbed this era as “The Great American Stomachache,” and for good reason. Imagine the average person’s diet in this time period. The average meal might consist of cured meats, unpasteurized dairy, pies, animal fats, starches, and grease, all washed down with coffee or liquor. You might have an ice box or larder to preserve your food, but there was no modern home refrigeration. There were no food safety regulations or quality assurance whatsoever. Store-bought foods were preserved with formaldehyde and sold from unsanitary meat-packing plants (Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle offers sickening details on the type of food safety hazards that were common in this period). Needless to say, there was a large market for products that could treat dyspepsia, including many that were marketed as cure-alls.

Alongside the expansion of his coal mining operation, the completion of the Little Book Cliff Railroad, and his Poland Springs water hitting store shelves, the years between 1892-1894 marked the halcyon days for Mr. Carpenter’s business enterprise. While his coal mining and coking operations produced the most profit, his mineral water and resort helped to draw outside attention to the community.

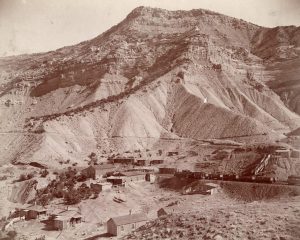

A view along the Little Book Cliff Railway from atop a train. The track wound through the dry Mancos shale badlands of the North Desert, along what is now 27 1/4 Rd. [Image courtesy of the Museums of Western Colorado]

That would have been an interesting legal battle had the business expanded as predicted, but the market had other plans. In May 1893, Carpenter’s ambitions came crashing into a brick wall as the nation underwent the most severe depression thus far in its history. Caused in part due to high tariffs on all foreign goods, railroad overexpansion, and the collapse of silver coinage, the Panic of 1893 caused consumers to rush to withdraw their money out of banks. With no capital, banks could no longer issue loans, leading to widespread business failure and a collapse in the stock market.

As someone whose primary industries were banking (though he resigned as president of Mesa County State Bank in 1889), mining, and railroad expansion, Carpenter was at the center of the largest industries hurt by the depression. By March of 1894 he was forced to lay off several of his men as result of the closure of silver mines in Aspen, which were the largest customers for his coal. Hoping to diversify his business, he once again returned his attention to building a resort, complete with baths, a lake, and lush park area.

The Rockaway Beach resort property is now part of the Lakeside community in Grand Junction. I apparently ignored the several “Private Property” signs when I came here to play as a kid. (Photo from Google Streetview)

For anyone who has visited the North Desert south of the Book Cliffs, “lush” is typically not the word that comes to mind, and though the mineral spring could sustain a bottling business, its flow of just 1 ½ gallons per minute was not enough to sustain the large lake he desired. He would have to start from scratch and choose a new location along the Little Book Cliff Railroad, which he found in the ridges north of Grand Junction in what is now a neighborhood south of Horizon Drive, in close proximity to the town’s canal system. Of course, he went with a name that already belonged to a locale on the east coast — Rockaway Beach (best known today from a song by the Ramones). He wisely changed the name to Lake Park before its opening in September.

The mineral water continued to be sold at least until 1896, according to Lyndon Lampert in a lecture to the Mesa County Historical Society, but it seemed to have lost any prestige it once had before then. Even Dr. Edward F. Eldridge, who continued to boost Grand Junction as a destination for health-seekers, made no mention of the mineral water or the resort in his nationally circulated essay Grand Junction as a Health Resort, published 1895. In fact, he seemingly downplayed his earlier assessments of its high quality, instead propping up a yet-undeveloped project to divert water from the Grand Mesa.

“Up to the present time we have been under the disadvantage of not having, for drinking purposes, the best of water, but our city is now constructing a pipeline from the mountains, at a cost of $250,000. This system will furnish the city with an abundance of the very best pure water from an altitude of at least 8,000 feet.” (Edward F. Eldridge, Grand Junction as a Health Resort, courtesy of the Museums of Western Colorado.)

Even though this plan was only in its conceptual stages by this point (and wouldn’t be completed for another thirteen years), Poland Springs simply couldn’t compete with Kannah Creek. It was all the same, since Susan Etta had made her husband destroy any remaining Poland Springs bottle labels to avoid infringing on the rights of the resort in Maine. (Little Book Cliff Railway, 43, see footnote. It’s unclear when exactly the labels were destroyed.)

Excursionists visiting the “Bungalow” house erected circa 1900. The excursion business continued for many years after W. T. Carpenter’s departure, but lacked the sort of resort accommodations that could be expected previously. [Image courtesy of the Museums of Western Colorado.]

While the mining operations and excursion business continued under new ownership, the resort venture and bottling works ended with Carpenter’s departure. He left Grand Junction to seek a fortune in the Klondike Gold Rush in the Yukon, never to return, leaving Susan Etta Carpenter alone to pick up the pieces and file for divorce in his absence (Little Book Cliff Railway, 148). A man once worth $100,000, Carpenter struggled to pull together even $400 to afford the trip (Little Book Cliff Railway, 141).

And thus, the mining town variously known as Carpenter, Poland Springs, or simply as the Book Cliff Mines faded into obscurity. It was nearly completely forgotten until it was rediscovered by teenagers Ed Helmick and Mike Kelley in 1962. What was left of the buildings were sold for scrap, picked apart by vandals, or simply decayed to rubble. The few ruins that remain give no indication that it was once planned to be a lush resort. There lie the lofty ambitions of William Thomas Carpenter, a man who was once the most enterprising pioneer industrialist in Mesa County, but is now little more than a footnote.

And on the pedestal these words appear:

“My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!”

No thing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

—Excerpt from Ozymandias, by Percy Shelley (1818)

_________________

Special thanks to Lyndon Lampert and Robert McCleod, whose research in Little Book Cliff Railway: The Life and Times of a Colorado Narrow Gauge formed the backbone of this project. Despite his prominence in the early days of Mesa County, Mr. Carpenter proved to be an elusive character to research, making this book a tremendous resource on the topic.

We’ve covered Carpenter a number of times before, so be sure to check out some of our other local history posts for more information.

- Finding The Little Book Cliff Railway

- A Ghost Town With an Alias

- Local History Thursday: Bookcliff Avenue and the Little Book Cliff Railway

- Nifty Names: Ghost Towns of Western Colorado

Our very own Ike Rakiecki has also given a talk on the Ghost Towns of Mesa County, which is available to watch on YouTube.

A sincere thanks to the Museums of Western Colorado for providing images.

Thank you for reading!

Thank you to the Friends of Mesa County Libraries for supporting Local History blogs like these.

Excellent work! Thanks.

Thank you!

Imagine you’re a worker in the “Satanic mills” (Blake) and other prison factories of the 19th century. Say you’re slaving away in Carpenter’s coal mine 12-14 hours a day, six or even seven days a week, not uncommon for exploited labor then (and still now). Add in his bankster bizzness and you’re unlikely to buy Carpenter’s concern for health as anything but another money-making scheme to get rich off other people’s backs. Especially since buying into the package deal at the health resort is entirely out of reach for your impoverished net worth as a commodity of labor power on starvation wages. You’re buried in the pit below the healing waters above where the better-off, one’s ‘betters’, bask.

Class oppression is not a pretty picture wherever its inhumanity prevails. Yet it is the principal cause of the illness and infectious disease we still suffer, and its alleviation if not abolition in whatever genuinely addresses public health (nutrition, sanitation, or any pollution-free environment like water once was) has been far more curative than any medicinal myth of germ warfare fighting human malady with antibiotics and vaccines.

Carpenter lived at a time when more naturopathic medicine was practiced. By now, we’ve been overtaken by so much of the money-making schemes of big bizzness like the Pharmafia drowning us in drugs, much to the harm of our health, that we keep buying the belief that ‘science’ has some snake oil to treat what ails us from a steady class war against the basic conditions of survival, let alone well-being.

What Upton Sinclair said of reading audiences’ reception of The Jungle – how it aimed for their hearts and ended up hitting their stomachs, as upper classes benefitted from regulations on the food industry while lower classes remained sunken in a sick society – is a fitting epitaph on all reforms and improvements which fail to go to the root of the cure we need in a more egalitarian and just society for us to not only survive but thrive.

Who built the seven gates of Thebes?

The books are filled with names of kings.

Was it the kings who hauled the craggy blocks of stone?

And Babylon, so many times destroyed.

Who built the city up each time? In which of Lima’s houses,

That city glittering with gold, lived those who built it?

In the evening when the Chinese wall was finished

Where did the masons go? Imperial Rome

Is full of arcs of triumph. Who reared them up? Over whom

Did the Caesars triumph? Byzantium lives in song.

Were all her dwellings palaces? And even in Atlantis of the legend

The night the seas rushed in,

The drowning men still bellowed for their slaves.

Young Alexander conquered India.

He alone?

Caesar beat the Gauls.

Was there not even a cook in his army?

Phillip of Spain wept as his fleet

was sunk and destroyed. Were there no other tears?

Frederick the Great triumphed in the Seven Years War.

Who triumphed with him?

Each page a victory

At whose expense the victory ball?

Every ten years a great man,

Who paid the piper?

So many particulars.

So many questions.

— A Worker Who Reads, Bertolt Brecht