Palisade, c. 1910. This is actually a cropped version of a stereo card depicting left-eye and right-eye views of the same scene. When placed into a stereoscope, the card would produce a three-dimensional image of the scene. [Image Source: Library of Congress]

Now that you’re salivating, how about some history?

The history of peaches in the Grand Valley closely follows the pioneer settlement of the region. Peaches were first cultivated in Eastern China and spread to Europe through the Silk Road. They were brought to the Americas by Spanish and English colonists, and eventually made their way west of the Rockies by American settlers. Peaches were among the first crops brought to the Grand Valley after the forced removal of Ute Indians in September 1881 – a move that violated a preexisting treaty. “A baptism of blood preceded the formal opening of the Ute reservation,” recorded the Daily Sentinel on September 13, 1900, “At the frontier towns waited an impatient people.” Eager settlers crowded frontier towns, such as Gunnison, waiting in anticipation for the Utes to be removed before making their way to the lush, fertile Grand Valley.

A drier section of Palisade with an orchard in the early stages of growth, near Mt. Garfield, c. 1900-1910. [Denver Public Library Special Collections, MCC-947]

One of the first settlers near Palisade was J. P. Harlow, who established a farm at Rapid Creek (~2 miles east of Palisade). Testing the capabilities of the valley’s soil, he planted a large vegetable garden and many fruit trees in the Spring of 1892. The vegetables yielded an impressive harvest, but the fruit trees died in large numbers. Continuing to experiment, Harlow fertilized the soil using burnt bones and leached ashes. His trees survived, and by 1885 they had started growing fruit. He continued to grow his farm, and by 1896, his orchard numbered over two-thousand peach trees in what may have been the first successful peach crop in the state of Colorado. Harlow shared his techniques with other horticulturalists, and from there orchards started popping up around the valley.

Peach orchards in Grand Junction and Fruita did not see nearly the same success, though both towns had sizable apple crops. It was apparent that there was something unique about the geography of the upper valley that protected its orchards from spring frosts. As it was soon discovered, Palisade’s location at the mouth of DeBeque canyon provides it with warm katabatic winds caused by the compression of warm air focused through the narrow canyon from a higher elevation. This “million dollar wind” spreads out as the valley widens, diminishing its effect on the lower valley.

From American Homes and Gardens, Vol. VII No. 1, page 118, published in January 1910.

Still, spring frosts were an ever-present concern, even with the advantage of Palisade’s unique microclimate. Inventive minds were put to work to eliminate this problem. In 1907, W. C. Scheu, a young inventor from Grand Junction, patented the first “smudge pot,” a small stack heater designed to keep orchards warm with slow-burning, smokey fuel, evenly spaced throughout an orchard. This ignited a competitive spirit in the Grand Valley as various inventors patented and showed off their modifications to the original design. Smudge pots also helped support orchards further into the lower valley beyond where the katabatic winds had no effect. By spring of 1908, thousands of smudge pots were employed in every orchard, causing “great clouds of smoke” to hang over the valley. Previous efforts to protect orchards from frost usually involved burning piles of manure at the early hours of the morning, so few complained about the heavy smoke from smudge pots.

Other notable innovations and patents included the use of stilts to prune tall fruit trees, a mechanical sorter used to sort peaches of different sizes into uniform boxes, electric brushing devices used to defuzz peaches, and specialized fruit picking sacks. Some of these were modified from older designs, but they all reflected the entrepreneurial problem-solving spirit of the valley’s early days.

In the days before photo editing software, clever compositing tricks were employed to make entertaining images like this postcard depicting implausibly large Palisade peaches, created c. 1940. [Photo scanned from my personal collection.]

The real centerpiece of peach season was – and still is, for that matter – the annual Peach Festival. Today, the tradition continues as the Palisade Peach Fest, but it was originally known as Peach Day and was hosted in Grand Junction. Peach Day started in 1887 as a local celebration of the valley’s early agricultural and demographic growth. “Only six years ago, [the Grand Valley] was a barren waste, where no white man was allowed, and only used for the Utes to roam over.” wrote Mrs. J. E. Phillips, a visitor and the wife of the editor of the Crested Butte Pilot, “Today, […] splendid farms in a high state of cultivation surround enterprising towns that have sprung up here and there all over it.” To be clear, early Peach Day celebrations reflected contemporary attitudes about the successful “civilizing” of so-called untamed lands by white settlers as much as it celebrated its agricultural growth. Bear in mind that 1887 also marked the opening of the Teller Indian School, where Ute children were stripped of their tribal identities and made to cultivate the land they were removed from in a misguided effort to “kill the Indian and save the man.” Those histories were closely intertwined in the early days of the Grand Valley.

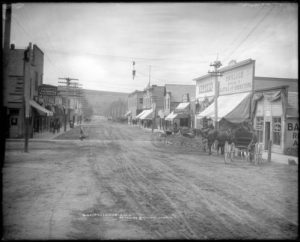

Palisade, c. 1900-1908. Palisade first incorporated as a town in 1904. [Denver Public Library Special Collections, MCC-851]

The surest sign that these efforts to boost the valley’s national profile had paid off came in 1909, when President William Howard Taft visited the Peach Day Festival as a guest of honor. It was a historic occasion not just because the President visited our small town west of the Rockies, which was rare in those days, but also because of a historic clashing of worlds. As he made his way through the fair, he was introduced to a company of notable Ute representatives, including Chipeta, Atchee, Chief McCook, George and Gerry McCook, and a young woman whose name was not recorded. He also met with some students from the Teller Indian School. It’s not clear what was said beyond cordial introductions.

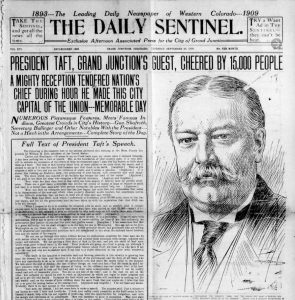

Taft’s visit dominated the September 23, 1909 issue of The Daily Sentinel.

15,000 people across all party lines attended the President’s speech as he lauded the Grand Valley’s transformation from desert to agricultural powerhouse, “You look at this country about here, at some places as we came down the canyon, and it seemed to me as if it was the most God-forsaken spot that there is on Earth. Then as you progress a mile or two and you see the influence of water, and it seems a paradise.” said the President, eliciting both laughter and applause, “No one can go through this valley without having his enthusiasm awakened for what man can do with nature when he acts upon scientific principles and pursues those principles with energy, industry, and proper self-restraint.”

In celebrating the development of the valley’s fruit industry, he also stopped to comment on the racial homogeneity of its growing population, “As the cheeks of your children show the same flush that your apples do, I infer that this air is as good for raising babies as for raising fruit,” he said, receiving applause and laughter from the crowd, “I do not hear any denial. Evidently there is no race suicide in this community.” One must assume the Utes in attendance had some thoughts about Taft’s comment that seemed to celebrate the racial purity in the valley as much as it celebrated the land itself.

The early history of peaches in the Grand Valley is filled with sobering moments like this, where the celebration of land and growth is linked closely to the injustices committed against the original inhabitants of this land. It’s true that the Grand Valley was transformed from arid desert to peach mecca, largely through the hard work, ingenuity, and resources of its early settlers. It is also true that this land was unjustly taken from its original inhabitants and transformed into something that it was never meant to be. That history is in the past, and it’s certainly not unique to our corner of the United States. It’s perfectly okay to celebrate our community, its culture and traditions, and the agricultural products grown here while also acknowledging that the past hasn’t always been so peachy. So eat a peach, thank a farmer, and don’t take any of it for granted.

Thank you for reading!

Outstanding Kris! Kudos!

Terrific story! I just spent some time interviewing the Talbott family about their history and the ups and downs of the peach industry in the valley. Your piece added interesting color to that family’s story. Thanks!

Hi Ryan,

Thank you for sharing! I’m always pleased to hear that my writing helps people gain a deeper understanding of the valley.

Kristen