[The Shadow of the Bottle, pub. 1915]

Powell, for his part, testified that he didn’t sell the bottle to Schultz, and believed he was doing a favor for a friend in desperate need of a drink. He explained that he took a dollar from Schultz and left it in an alley in a nondescript spot. Twenty-five minutes later, the dollar had been replaced with the beer. His lawyer successfully argued that Schultz had enticed him into committing the crime, and was even able to get the tampered bottle removed as evidence. Even still, Powell could not escape the long arm of the law, and the guilty verdict was upheld. The message was clear: if you break the law, you will spend exactly ten days in county jail before being released. Better sleep with one eye open, bootleggers.

Let’s back up a bit. My two most recent Local History Thursday posts, Temperance and the Colorado Frontier and Ute Removal and the End of the Colorado Frontier, both centered on the temperance movement in Colorado during the 1870s and its impact on immigration, town building, and Ute Removal. William Pabor, one of the temperance advocates discussed there, went on to found the town of Fruita as an agrarian temperance colony in the former Ute reservation. From its very foundations, Mesa County was a friendly environment for like-minded tee-totalers.

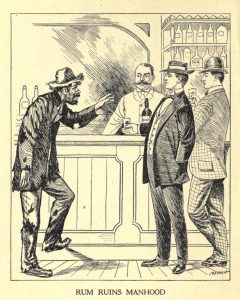

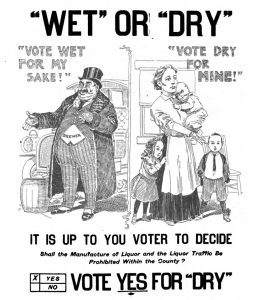

Prohibitionist propaganda often highlighted the detrimental effects of alcohol abuse on the family. [Ohio State University]

Colorado gave women the power to vote in 1893, and they relied on the W.T.C.U. and church organizations to exert political power. At the time, public drinking was considered a strictly male activity. A saloon, with its gambling, prostitution, and other vices was simply no place for a lady. In contrast, women and children were often the primary victims of a husband abusing alcohol. In an era where women were economically dependent on their husbands, prohibition was a major priority.

The prohibitionist cause was also aided by old-fashioned racism and xenophobia. The saloon was a place where America’s working class, immigrant, and nonwhite communities could gather, converse, and develop political consciousness. From 1880 to 1930, more than 23 million people immigrated from places like Germany, Ireland, Italy, Russia, and Poland – all of which were stereotyped as lazy, stupid, and drunk. The urban slums and working class neighborhoods these immigrants flocked to were looked down upon as hives of immorality. Black, indigenous, and Hispanic working class communities were also frequent targets of prohibitionists. It’s no coincidence that the Ku Klux Klan emerged as a dominant political force during the era of national Prohibition; both the KKK and the prohibitionists were primarily white Protestants who felt threatened by the growing political power of the nation’s underclass.

By 1909, the prohibitionist cause had grown large enough to appear on the ballot in Mesa County. Despite heated discussion surrounding the measure, it ended up being a blowout for the prohibition side. Of the 2,392 votes cast, 1,823 (76%) voted to make Mesa County dry, with only 569 (24%) voting against. Due to its population, Grand Junction was excepted from this initial vote, making it the only “wet” territory within the county. It only lasted five months, when Grand Junction voted 1,480 (59%) yes to 1,009 (40%) no in April 1909. The wets suffered further losses in November that year when Grand Junction voters elected a prohibitionist mayor, city clerk, and four aldermen.

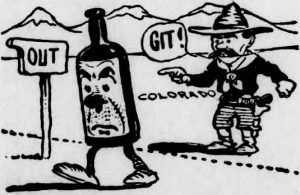

Mesa County voted to prohibit alcohol in 1909, and the State of Colorado followed suit in 1915. [Idaho Springs Siftings, March 3, 1916]

If Doc Powell’s sentence of ten days in county jail was intended to dissuade bootleggers, it had the opposite effect. By banning the sale of alcohol, prohibitionists inadvertently created a thriving black market willing to meet the demand at any price they wanted. Even when convicted, the harshest sentences were no more than ninety days in jail or $200 in fines for each charge. While $200 was nothing to sneeze at (roughly $6,300 in today’s money, adjusted for inflation), it also wasn’t enough to deter a sufficiently profitable rum-running operation, especially if the bootlegger was back on the street within three months. There was serious money to be made.

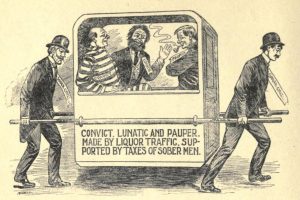

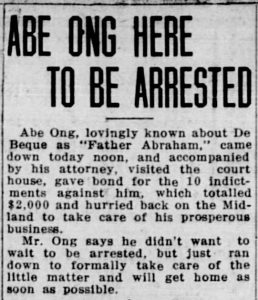

Even when bootleggers were caught, charged, and imprisoned, it was up to the taxpayer to foot the bill. Abe Ong was once described as “an expert in at working the county for a free meal ticket.” [The Shadow of the Bottle, pub. 1915]

In one raid in which Abe and nine co-conspirators were arrested, police discovered bottles of whiskey stashed away in dresser drawers, a sewing machine, under floorboards and heaps of coal, in typewriter desks, and even under a sleeping baby resting in a carriage. In another case, Ong tried unsuccessfully to flip the script and have the Chief of Police arrested for burglary after he seized a barrel of beer, several bottles, and a revolver from him. By my (admittedly incomplete) survey of arrests recorded in Colorado Historic Newspapers, Ong was arrested at least thirteen times at his peak between 1911-1918, during which he spent a minimum of fifty months behind bars.

Rather than wait to be arrested, Ong once made a trip down to Grand Junction to pay a $2,000 bond (about $62,466 adjusted for inflation), then immediately returned back to De Beque to “take care of his prosperous business.” [Daily Sentinel, October 27, 1913]

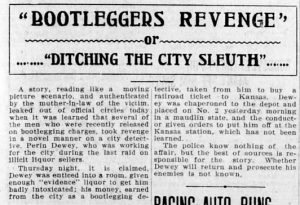

That said, the legal system hardly needed someone like Abe Ong to expose its failures. In some cases, the detectives hired to catch bootleggers were far worse than the bootleggers themselves. Take Perin Dewey, a brick mason who moved to Grand Junction in 1911 after serving time in the Oklahoma State Penitentiary. At the age of 27, he married Dolores Harris, a 16-year-old waitress whom he had only known for a single week. Within three weeks, he threatened to blow her head off in a drunken rampage for going to Salvation Army meetings, then nearly drank himself to death after she asked for a divorce. For whatever reason, the City of Grand Junction then chose him for detective work just a few short weeks later.

As a detective, Dewey’s job was to purchase liquor and turn it in to the Chief of Police. Dewey was great at the first part, but was less reliable on the second. On August 22, 1912, several bootlegging cases were dismissed after Dewey drank all of the evidence – a screw up so bad that it even got him chastised by the defense attorney, “You ought to be back in the Oklahoma penitentiary.”

[Daily Sentinel, August 31, 1912]

On September 5, it was reported that Perin Dewey died after falling beneath a moving freight train in Pueblo. His remains were mangled beyond recognition, and were only identifiable as Dewey due to a letter found on his person. On September 12, however, Perin Dewey defied death to vow vengeance on whoever drugged him. As it turned out, his alleged death was a hoax perpetrated by the same bootleggers. It’s not clear if he ever enacted his vengeance on the perpetrators, because he seemingly disappears from the newspapers after this. Perhaps he was intimidated into staying out of town, or perhaps those bootleggers found a more permanent means of disposing of the troublesome detective.

There were no shortage of corrupt officials willing to turn a blind eye to bootlegging. In Palisade, the town’s mayor, four aldermen, and town marshal were all opposed to enforcing Prohibition. Marshal Moore was frequently spotted wandering the streets in such “an intoxicated condition” that “he could not keep on the sidewalk.” One restaurant in Palisade, the Eagle Cafe operated by James and Charles Ferguson, sold liquor in plain daylight to anyone willing to pay. Certain townsfolk grew frustrated with the inability of their officials to enforce the law, and on the evening of July 10, 1911, a group of fifty masked men armed with rifles and shotguns arrived at the Eagle Cafe to deliver an typewritten ultimatum:

“Warning to James M. Ferguson: Within ten days from July 10, 1911, you MUST close your business, and take your family and leave this town and NOT return. You will be dealt with AT ONCE for any insult, abuse, or violence by yourself or wife towards any citizen of this town during the ten days. GET BUSY.” Signed, Law and Order League (Wicked Western Slope, p. 66-67)

As the word spread quickly around the Valley, Sheriff Schrader assured everyone that mob violence would not be tolerated in Palisade. The scandal even caught the attention of the Governor, who demanded that Schrader keep things under control. The Fergusons appealed to the town council for protection, but one alderman, G. M. Hand, reminded the men that they had once before assaulted him in his own office for interfering in a previous bootlegging matter. While the Fergusons insisted they would not be intimidated into leaving, when the deadline came on July 20, they were gone. Citizens had to face the uneasy reality that violent bands of armed men were more effective at enforcing the law than their own local government.

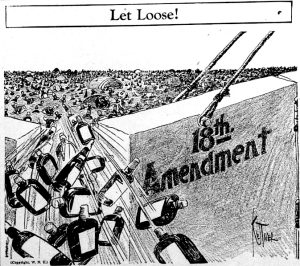

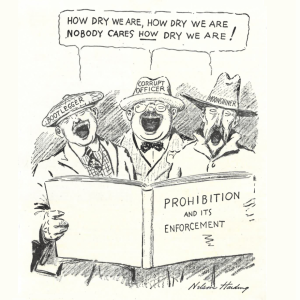

By the time prohibition went statewide in 1916, then national in 1920 following the Eighteenth Amendment, Mesa County was already disillusioned with the futility of enforcing such a law. Alcohol remained abundant to those who sought it out, all while criminals profited and made a mockery of the justice system. Did 16-year-old Dolores Harris feel safer knowing that the liquor her husband drank before threatening to kill her was now illegal? Did the masked vigilantes who marched through the streets of Palisade bestow a sense of law and order? Did citizens feel confident in their justice system after watching Abe Ong walk free again and again?

The ratification of the Twenty-first Amendment in December 1933 marked the end of Prohibition. [Palisade Tribune, December 8, 1933]

“We know of nothing that has developed such hypocrisy as the prohibition era. Now it will no longer be necessary for some of our prominent citizens to lead double lives, addressing W.C.T.U. meetings by day and ‘partying’ by night. It will no longer be necessary for a politician to vote dry as he drinks wet.” (Daily Sentinel, December 8, 1933)

For Walter Walker – arguably the most well-connected man in Grand Junction at the time – to admit that even some of the law’s most prominent supporters were drinking in secret, it meant that Prohibition was truly a failure. The same lips that paid service to the dry cause in public were paying to get drunk in private. In the end, the only ones left to mourn the demise of Prohibition were the career bootleggers forced into an early retirement.

_________________

Thirsty for more? I recommend the article “Women, Politics, and Booze: Prohibition in Mesa County, 1908 – 1933” by Jerritt Frank from the Fall 1999 edition of the Journal of the Western Slope and the “Prohibition Punch” chapter of Wicked Western Slope by D.A. Brockett. Additionally, the Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection and the Mesa County Oral History Project are, as always, invaluable resources for this type of research. I think there’s still more to say here about Prohibition, so maybe we’ll revisit this topic some time in the future.

Any thoughts to share, perspectives to add, or anecdotes to offer? Please let us know in the comments!

Thank you for reading, and please drink responsibly!

Thank you to the Friends of Mesa County Libraries for supporting Local History blogs like these.

Thank you to the Friends of Mesa County Libraries for supporting Local History blogs like these.

Great story. Couldn’t put it down!