Read part two, “Ute Removal and the End of the Colorado Frontier”

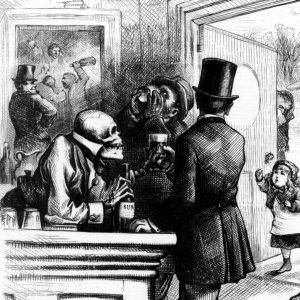

“The Bar of Destruction” by Thomas Nast [Harpers Weekly]

Temperance, or abstinence from alcohol, was among the largest political causes in the mid-to-late nineteenth century, long before nationwide prohibition in the 1920s. It wasn’t just teetotaling evangelicals who promoted temperance, but a broad coalition of progressive social reformers, public health advocates, and religious organizations in the mid-to-late nineteenth century. The movement went beyond advocacy for moderation or personal abstinence, its purpose was the elimination of all liquor from American life. They argued that alcohol, even in moderation, degenerated the mind, body, and spirit, and was the root of all social evils, from spousal abuse to indulgence in sin. Much of these efforts were focused on immigrants from Ireland, Germany, and Italy.

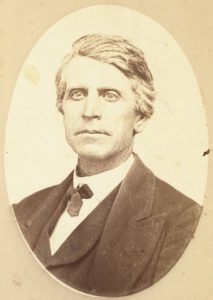

Horace Greeley c. 1860-1865. [Public Domain]

In 1869, Greeley had the opportunity to sponsor such a community in Colorado, organized by a fellow temperance man, Nathan Meeker. Born in Ohio in 1817, Meeker had difficulty sticking to one job throughout his life. He worked at various points as a farmer, teacher, traveling salesman, poet, store owner, librarian, and secretary, all to minimal success. In 1843, he joined the Trumbull Phalanx Colony in Ohio, an agrarian commune based on the socialist principles of Charles Fourier, but he left in 1847, disappointed with the colony’s failure to produce a profit. He later opened a store in Hiram, Ohio, which found moderate success through liquor sales. Despite his temperance views, he seemed to see no inconsistency with selling it if he could make a profit. This was quickly put down by local religious authorities, and Meeker lost his store shortly after, disillusioned and bitter.

Portrait of Nathan Meeker, unknown date. [Public Domain]

Meeker possessed a firm belief that he would die at age sixty, and endeavored to “do something of significance” with his limited time (The Utes Must Go, p. 72). He achieved his first big break in the mid 1850s after Horace Greeley agreed to republish his agricultural essays in the Tribune. Impressed with his work, Greeley assigned Meeker as his war correspondent in southern Illinois after the outbreak of the Civil War. After the war, Meeker was hired full-time as the Tribune’s agricultural editor.

In 1869, Meeker was sent out west to find a suitable location to establish a colony for Greeley. Meeker proposed a site in northeastern Colorado at the confluence of the Cache la Poudre and South Platte Rivers, and the duo drafted a charter for the Colorado Union Temperance Colony, otherwise known as Greeley. This colony was intended to be a model for western settlement, demonstrating the viability of a planned community built on cooperative farming and reformist principles.

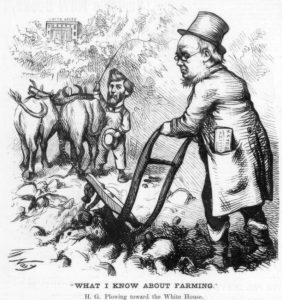

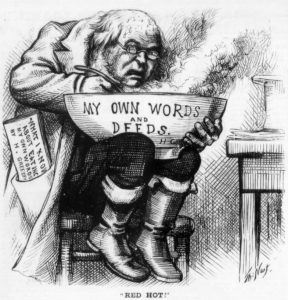

Cartoonist Thomas Nast satirized Greeley’s claims of expertise on farming and other subjects. This cartoon depicts him plowing a rocky path bound for the White House, referencing his book What I Know of Farming. [Harper’s Weekly]

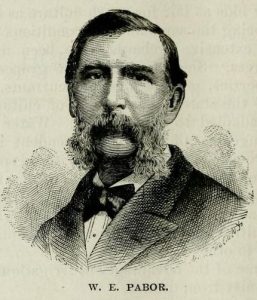

One of the original colonists was a man named William E. Pabor. Like Meeker, Pabor was a poet and newspaper editor who admired Horace Greeley. By all accounts, Pabor was a much more successful wordsmith than Meeker. Born in Harlem, New York in 1834, he became a published poet by age sixteen and became editor of the Harlem Times weekly newspaper at nineteen. While his poetry is obscure today, he would have been considered a relatively famous poet in his time. A fellow temperance activist, agriculturalist, and active Tribune reader, Pabor was the first person to respond to Meeker’s call for applicants and climbed three stories to personally greet Meeker in his office at the Tribune. At the Union Colony, Pabor acted as secretary.

Portrait of William Pabor, unknown date. [Printed in The Great West: A Vast Empire, 1889]

To make matters worse, a major drought and grasshopper infestation further devastated the community during its first growing season. Meeker’s attempts to build an advanced irrigation system ended up flooding more basements than fields – in addition to throwing the town into deeper debt (The Utes Must Go, p. 84). Within a year, more than half of the original colonists demanded a refund, with one former colonist writing that the project “is a delusion, a snare, a cheat, a swindle, … a graveyard in which are buried heaps of bright hopes and joyous aspirations.” Father Meeker’s flock was starting to lose faith. “Those were dark days for colonization in Colorado,” Pabor would later reflect.

In neighboring Evans, saloons and dance halls impeded any efforts to keep the colony free of liquor. Outraged to hear that men from the colony had been spotted there, they targeted a saloon owned by Fritz Neimeyer, a Prussian immigrant. A group of men were sent to negotiate with Neimeyer to leave his property, but while arrangements were still being made, a fire broke out, incinerating the building. Neimeyer’s livelihood was in ruins. Meeker’s son Ralph was one of several colonists arrested for riot and arson in the aftermath. Ralph fled town, and while he was gone, the court papers mysteriously disappeared. No one suffered any legal consequences for this action, but the scandal demonstrated how far the colony was willing to go to enforce its prohibition on the “demon rum.”

A Colorado prairie home from a chapter about Greeley in Pabor’s book on Colorado agriculture. [Colorado As An Agricultural State]

Horace Greeley grew more impatient as the colony accrued debt, and gently suggested that Meeker step aside to allow someone else to govern. Ever unyielding, Meeker remained in his position and Greeley, ever permissive, did not press the issue further. In hopes to generate some kind of profit, Meeker received another loan of $1,500 from Horace to establish the Greeley Tribune as the town’s paper, with himself serving as the editor-in-chief. This mostly served to place Meeker into further debt with Greeley and continue to distract him from his official duties. The Greeley Tribune often featured lengthy tirades about politics, liquor in the colony, and his new favorite cause of vegetarianism. It’s hard to imagine the colonists, already struggling to grow food, much appreciated Meeker’s polemics against eating meat, nor did the paper’s moralistic bent help to attract many new colonists. (The Utes Must Go, p. 86-87)

Greeley, who for decades was a vocal critic of the Democratic Party, allied with them for his 1872 presidential bid to defeat Ulysses S. Grant. This cartoon by Thomas Nast depicts Greeley choking down his former words and deeds. The paper in his pocket reads, “What I Know About Eating My Own Words.” [Harper’s Weekly]

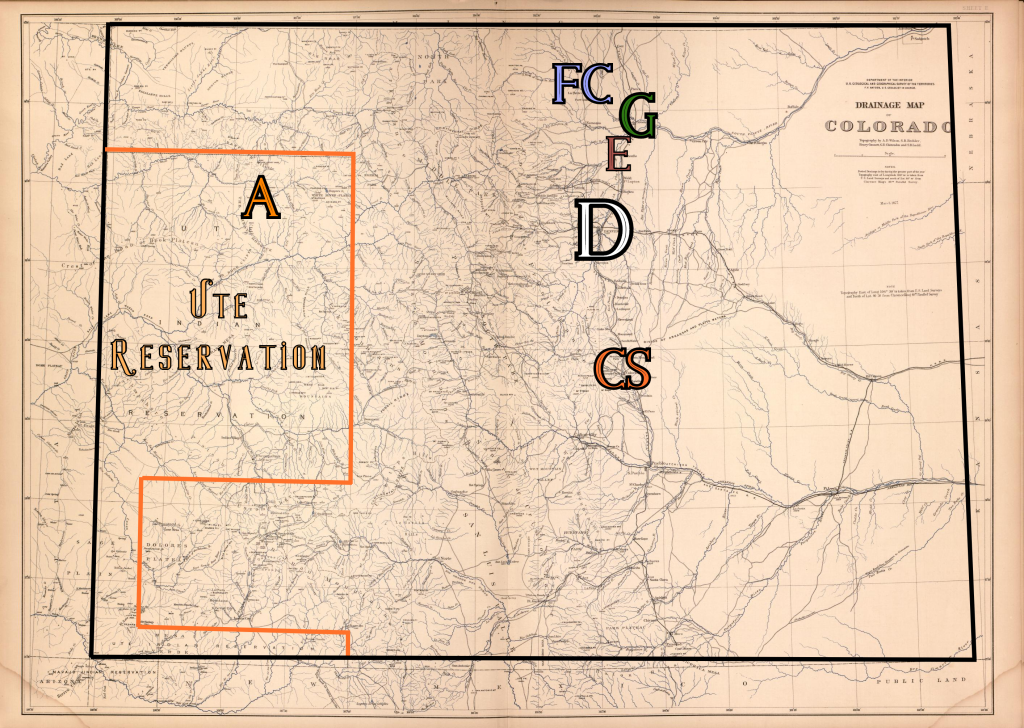

Pabor didn’t stick around long enough to see what the colony looked like after Greeley’s death. By May 1871, he had already moved on. He became secretary for another temperance project in 1871, the Fountain Colony, better known today as Colorado Springs – a name given by Pabor. Two years later, Pabor also helped to organize the Fort Collins Agricultural Colony and was involved with its incorporation as a dry town in 1873. Pabor also helped to secure Fort Collins as the site of the Colorado Agricultural College (Now Colorado State University), a prize that Meeker desperately wanted for Greeley. He was an accomplished author and promoter of Colorado agriculture during this time, serving as the associate editor for the Colorado Farmer and writing columns for various newspapers, in addition to his successful poetry. Everything Meeker did, it seemed, Pabor did better.

In 1877, Meeker, increasingly desperate and in arrears with Greeley’s estate, made the decision to leave Greeley. In that time, Colorado was admitted as the 38th state in the Union, opening up many new opportunities for a man like Meeker to pay his debts and save his reputation. He tried running for office, but found no goodwill among Republicans in the state. He applied for an appointment to become Colorado’s postmaster, but received no response. He then submitted his name for appointment as American Agricultural Commissioner to the 1878 Paris Exposition, but was also ignored.

Meeker took notice of an opportunity to work as the Indian Agent for the White River Ute Indian Agency, which offered a considerable annual salary of $1,500. He petitioned Colorado’s senators – both Grant Republicans – to recommend him for the job. The Utes were considered a problem to be removed or exterminated by most Colorado politicians, but Senator Henry Teller was a strong proponent of the assimilation of Utes into white society. Though Meeker was viewed as somewhat of a liability, Teller found his ideas on assimilation to be agreeable, and believed that he was the right candidate to bring agriculture, Christianity, and temperance to the Utes.

Meeker would spend the rest of his life pursuing that goal.

For now, we’ll have to leave the story there. This next chapter of Colorado history is significant enough to demand its own in-depth Local History Thursday. Please stay tuned for part two, where we’ll discuss Meeker’s turbulent tenure as Indian agent for the White River Indian Agency, his death, and how temperance applied to ideas of Manifest Destiny on the Colorado frontier. It should hopefully become clear how all of this history on the Front Range ties into our local history here in Western Colorado.

Read part two, “Ute Removal and the End of the Colorado Frontier”

Colorado circa 1877, edited to highlight relevant points of interest. A: White River Ute Indian Agency, FC: Fort Collins, G: Greeley, E: Evans. D: Denver, CS: Colorado Springs. [Library of Congress, edits by author]

This is one of those times where I started researching one topic and ended up uncovering something entirely different. Originally, this was going to be narrowly focused on the Prohibition Era in Western Colorado. I had already known that William Pabor prohibited alcohol when he founded the City of Fruita, and wanted to delve deeper to add some historical context to his views on temperance. As it turned out, that rabbit hole went much deeper than I had anticipated. Stay tuned for that Prohibition Era post sometime in the future.

As always, thank you for reading.

I gots some sources for you on this I have some microfiech copies of The Church News, the local WCTU paper 1908. And some sources on the racial nature of prohibition enforcement locally.

Thank you! I would certainly be interested in looking at those for when I write my piece on Prohibition.

I had no idea about most of this history. I found it interesting, even entertaining! Keep up the good work!

Thank you!