Color photograph of the Trinity nuclear test, the first detonation of a nuclear weapon during the Manhattan Project. Following the test, Project Director Kenneth Bainbridge remarked, “Now we are all sons of bitches.” [U.S. Department of Energy]

Congratulations, you’ve just set off a nuclear bomb!

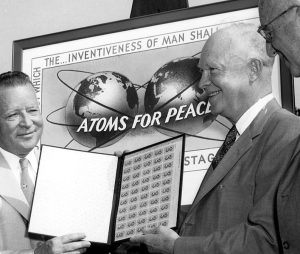

If you’re anything like the United States government during the Cold War, you’re probably feeling pretty conflicted. On one hand, you’ve just developed the most powerful weapon ever imagined, capable of leveling entire cities and killing hundreds of thousands in a single bright flash of light and radiation. On the other hand, the Soviets also have nuclear weapons, and the only thing preventing them from doing that to your own citizens is the fact that doing so would mean mutually assured destruction. In December 1953, President Eisenhower publicly acknowledged the “awful arithmetic of the atomic bomb” and called for international cooperation in finding peaceful uses for nuclear technology in his famous Atoms for Peace speech. Arguably, it was just political cover to accelerate the arms race, but there was a sincere hope that this technology could be used to benefit mankind.

By the 1960s, both nations and their respective allies had enough nuclear weapons stockpiled to render massive corners of the planet uninhabitable. In the interest of easing public fears about the dangers of nuclear weapons, the United States Atomic Energy Commission made plans to search for peaceful, non-combat use for nuclear explosives.

President Eisenhower promoting “Atoms for Peace” stamps, c. 1955 [U.S. Department of Energy]

That takes us to Rulison, a small unincorporated community near Parachute, Colorado (known as Grand Valley at the time) off of I-70. It was estimated in 1965 that the Mesaverde geologic formation located near Rulison contained an estimated eight trillion cubic feet of natural gas located in depths ranging from 6,200 to 8,700 feet beneath the surface, across some 60,000 acres. At those depths, “conventional production stimulation methods” for natural gas extraction were made “impractical and uneconomical.” (United States Atomic Energy Commission, Project Rulison Manager’s Report, 1). With that in mind, the Atomic Energy Commission had one question; could nuclear explosives be used to liberate natural gas from deep underground deposits?

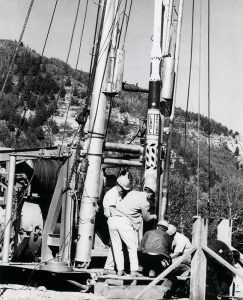

Workers lower the 43 kiloton nuclear explosive into the 8445 ft emplacement hole at Project Rulison, c. 1969. [U.S. Department of Energy]

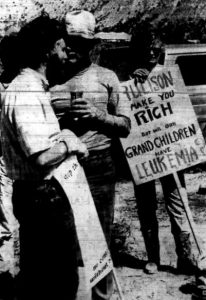

Demonstrators from Aspen protest Project Rulison. They held up signs reading “Rulison will make you rich but will our grandchildren have leukemia?” and “No contamination without representation.” [Daily Sentinel, September 11, 1969]

For Project Rulison, stage one of testing involved drilling a hole 8,425 feet deep (about 271 feet below sea level) and conducting geological and hydrological studies, as well as testing the gas productivity of the well before the blast. In stage two, the 43 kiloton nuclear payload – nearly three times as strong as the bomb dropped on Hiroshima, and equivalent to 43,000 tons of TNT – was lowered into the hole while encased in a 10 ¾ inch steel casing. After the explosive was lowered in, the hole was backfilled with course material to essentially plug it closed, preventing any gasses or radioactive material from escaping. Then, at 3 p.m. on September 10, 1969, the big moment came… KABOOM! (Project Rulison Manager’s Report)

For about five seconds after detonation, the earth “shook like jelly” (CBS Evening News, September 10, 1969), kicking up dust and knocking rocks loose from the surrounding mesas. Small rock slides briefly closed stretches of highway through De Beque Canyon, the Rifle Gap, and Glenwood Canyon. Homes in Rulison and Parachute had shattered windows and collapsed chimneys from bricks being knocked loose. People in Grand Junction anticipated the blast by stacking towers of coins, which collapsed spectacularly as the shockwave reached the valley. In Golden, students at the School of Mines recorded tremors reaching 5.5 on the Richter scale just 40 seconds after the blast. And yet, despite all of the disturbance, the test went more-or-less entirely as expected by the Atomic Energy Commission. For many, it was actually a bit of an anticlimax. (The Daily Sentinel, September 11, 1969)

Cross section of the Rio Blanco test site depicting the three nuclear blast cavities. Molten glass from the blasts cooled at the bottom of each cavity, blocking chimney access to the bottom two cavities. [U.S. Department of Energy, Radionuclide Migration at the Rio Blanco Site, 10]

Project Rio Blanco followed the same stages as Project Rulison, but with three nuclear explosives lowered at distances of 5840, 6230, and 6690 feet. The bombs were detonated on May 17, 1973. Despite the heavier payload, the results were fairly similar to the previous test, with seismic activity recorded at 5.6 on the Richter scale and minor property damage to surrounding areas. Many observers actually reported that the shockwave felt less powerful than the Rulison blast.

Ultimately, both tests were considered technical successes, with surveys showing that there had been no groundwater contamination and only small amounts of radiation released into the atmosphere after the wells were reopened. Soil and nearby natural gas wells have also been sampled for radioactive isotopes, but nothing out of the ordinary has been found. As far as the Atomic Energy Commission is concerned, with regular ongoing testing supporting this conclusion, the tests were conducted with utmost safety with minimal impact on the environment.

“No gas, huh?” This cartoon was published in the student newspaper at the University of Colorado Boulder after Project Rio Blanco produced disappointing results. [Colorado Daily, February 28, 1974]

While the tests were successful on a technical level, the actual objective of the tests – to see if nuclear explosives could be used to liberate usable natural gas from otherwise inaccessible deposits – was a failure. Sure, it was proven that you could use nuclear bombs to create natural gas wells, but what good is irradiated natural gas? In the end, not a single cubic foot of natural gas from any of the tests was ever sold to consumers.

In 1974, a State Constitutional Amendment was introduced to prohibit the detonation of nuclear devices in Colorado without first receiving voter approval. Voters approved the measure with 58% in favor, largely fueled by voters on the Front Range, but the measure was also approved by voters in Rio Blanco and Garfield Counties, where these tests took place. Mesa County, on the other hand, rejected the measure. They don’t call us mavericks for nothing, I suppose.

In any case, the passing of Colorado Amendment 10 showed that if anything, attempts to find peaceful uses for atomic explosives had made the public more weary of nuclear weapons, not less. Funding for Operation Plowshare ended in 1975, and the program was officially terminated in 1977. Since then, interest in nuclear explosives, testing, and energy has significantly declined. Nuclear Armageddon barely even registers as a significant existential threat to most people these days. The atomic age is well and truly over.

Today, all that remains of Rulison Ground Zero is a site marker and a plaque placed there by the Department of Energy. It remains on private property, so whoever snapped this photo probably wasn’t supposed to be there. You can read the plaque here, if you’re interested. [Wikimedia Commons]

If nothing else, it was a nice thought. In a time when the atomic age was moving at a fearful pace, there was hope that nuclear explosives could be used to advance human life rather than destroy it. As President Eisenhower phrased it in his Atoms for Peace speech, these tests were part of a sincere effort to find “the way by which the miraculous inventiveness of man shall not be dedicated to his death, but consecrated to his life.” As we find ourselves in a new era of rapid technological advancement, we can learn a lot from that dedication to progress, human welfare, and peace. With any luck, maybe those future efforts will involve fewer bombs.

_________________

For more Project Rulison, you should definitely watch this declassified film produced by the Department of Energy. Not only is it a remarkable time capsule, but it also includes some great information and visuals about the project. It also includes plenty of cool vintage cars and shots of Parachute and its surrounding geography.

Did we miss anything important? Do you have memories to share? Did I get the nuclear science totally wrong? Please let us know in the comments!

Thank you so much for reading!

The “protest were only by Aspen/Boulder/Denver liberals” myth isn’t 100% true. There were local protesters. Chuck Worley of Cedaredge. Protested both. Including acts of Civil Disobedience in protest to Project Rio Blanco. https://archive.storycorps.org/interviews/mby004371/

Chester Mcqueary of Parachute was involved in what the Sentinel called a “hippy chase” at Ground zero of project Rulison. His first-person account of being on the mtn when the bomb went off, is here. https://www.hcn.org/issues/25/727.

These acts of civil disobedience and wanton pillage added momentum to very small local environmental and anti-Vietnam and anti-nuke movements in the Grand Valley.

Hi Jacob,

Thank you for this additional context and for including those fascinating primary sources. It’s certainly true that these tests were opposed by the majority of local residents, which is reflected in the election results for the Colorado Detonation of Nuclear Devices Amendment. Even Mesa County, which opposed the amendment, was split 48%-52% on the issue (Delta County, the only other Western Slope county to oppose the amendment, had a similar split). The protesters from Aspen, Boulder, and Denver were definitely given a lot more attention by the media, which tended to overshadow any local sentiments (as is too often the case).

Thank you for sharing these perspectives,

Kristen