Some criminals achieve fame through cunning, working as masterminds and manipulating law enforcement to evade capture for as long as possible. Others become famous through building criminal empires, creating massive gangs that can rival multinational corporations in scale. Others, like Mesa County’s pioneer bootlegger, Abe Ong, seemingly become famous through sheer audacity.

In my last Local History Thursday, Prohibition in Mesa County, I briefly discussed Abe Ong, a bootlegger from the county’s Prohibition Era who became notorious for his frequent and repeated arrests for the same crime, both a reflection of his own stubbornness as well as the inability of local authorities to get a handle on bootlegging. I must confess that what started as background research quickly grew into a fascination, and I ended up learning far more than I could reasonably include in just one post. Abe Ong lived an incredibly rich life even before taking up bootlegging at the age of fifty, and the twenty years he spent rum-running in Western Colorado provide a multitude of amusing stories.

Not much is known about Abe Ong’s early life. He comes from a notable family of early American colonists who arrived in Boston in 1630 from the village of Lavenham in England. Many of the Ongs were rather famous in their own right, but Abe’s father, Jesse R. Ong (b. 1837) was evidently a bit of a black sheep within the family. His section of the family tree doesn’t appear in the official Ong Family of America genealogy compiled in 1906. From what I could gather from more contemporary genealogies, Jesse Ong married Lucretia Croft in Marshall County, IL in December 1855. In 1859, the happy couple had their first child together, Abraham C. Ong. In 1870, when Abe was eleven years old, Lucretia divorced Jesse, citing adultery. Abe stayed with his mother through his adulthood.

In 1892, Abe moved to Lafayette, Colorado to work as a coal miner. In September 1894, Abe saved the life of his superintendent, C. S. Otis, by disarming a man wielding a shotgun who had come to kill Otis for refusing to hire him. By 1896, he took on a role as Secretary of the Lafayette Miners’ Union, and was active in strikes that year organized by the Western Federation of Miners. While in Lafayette, Abe also opened a saloon, which is notable because Lafayette happened to prohibit alcohol within the original town plats. There was no evidence to suggest he sold alcohol in any illegal zones, but even at this time, Abe made it his business to get drinks to people who might not otherwise be able to.

Abe’s second cousin, Judge Joseph E. Ong, was a prominent Democrat politician in Colorado and Nebraska, and briefly represented Mesa County in the Colorado State Legislature. He was the primary developer of the Bluestone Valley in De Beque, where Abe moved in 1900. [Rocky Mountain News]

In September 1900, while Abe was away on a hunting trip, Emily abruptly left with their son George to Streator, IL, where her family was from. Unable to receive an explanation or encourage her to return to De Beque, Abe filed for divorce. Emily’s deposition, read by her lawyer in her absence, revealed many interesting details about their marriage.

Emily described her husband as having a character of “brutality, indecency, inebriety, and general grossness that would be hard to match.” He frequently wore his clothing, both outer and under, for so long without changing that “the odor radiating from his person put him in the category with certain four-legged animals.” He rarely bought new clothes for himself, Emily, or their baby, and was generally a poor provider. For Abe’s part, he blamed Emily’s sister Jennie, who he would get into vulgar shouting matches with whenever she visited. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the court ruled in favor of Emily, and Abe was required to pay $154.93 plus the costs of the suit. Emily would never remarry, and their son grew up without knowing his father.

In the years following, Abe mostly kept his nose clean. He worked odd jobs, mostly ranching at mining. In 1904, his mother Lucretia died and was buried in De Beque. In 1905, Abe began working as a cocktail mixer at the Silver Club Saloon in De Beque. While Mesa County voted for Prohibition in 1909, Abe stayed out of trouble, possibly due to the scrutiny of his cousin, Judge Joseph Ong. Judge Ong was badly injured by an automobile in late 1908, and his mind and body steadily declined until he passed away on November 4, 1911. It was only in the last year of the Judge’s life, infirm and senile, when Abe finally turned to bootlegging.

Given the underground nature of Abe’s enterprise, it’s difficult to pin down exactly when it started, but his first arrest came in the summer of 1911, when he was about fifty years old, for “running a disorderly house,” the charge for running a speakeasy. According to The Plateau Voice, “Witness after witness brought down from De Beque testified [they] had been buying beer whenever [they] wished it at Ong’s place” in an operation that had been going on for several months. He sold beer for 25 cents a piece, which was about 10-20 cents over the usual price. Ong was found guilty after just five minutes of deliberation without any arguments from the prosecution. He served time between August 4 and December 22, 1911, when he was released for good behavior. Abe wasted no time returning to his bootlegging business.

In May 1912, Abe was served five grand jury indictments for bootlegging. Abe was released on bail and continued his business as usual. In August 1912, Abe Ong’s pet bulldog got loose and went on a rampage in De Beque, personally ripping and tearing through over 78 chickens before being put down by the town marshall.

In October, while awaiting trial for his grand jury indictments, Abe found himself at the center of a local political scandal. The Grand Junction News, a Republican Bull Moose paper, sent a reporter named Emmett Fuller to go undercover and purchase liquor at Ong’s club, something he achieved with minimal effort. He described Abe’s shack as being littered with “more or less five hundred” empty beer bottles, and blamed Sheriff Schrader, a Democrat, for neglecting to crack down under such flagrant disregard for the law. [Grand Junction News, October 5, 1912] Fuller was additionally chosen as the chief witness for the prosecution in Abe’s trial, and provided the liquor he purchased as evidence.

The Daily Sentinel, at the time a sternly Democrat paper, responded by accusing Fuller of “concocting” evidence to “suit a dirty, vicious, and lying attack on Sheriff Schrader in an effort to defeat [him] for re-election.” This resulted in weeks of mudslinging between the two papers until the election in November, where Schrader handily won reelection in a race that delivered historic victories for the Democratic party. The Grand Junction News summarily dropped the story. When it came time for Abe’s trial, his lawyers seized on the narrative that Fuller was entirely motivated by a partisan desire to attack Sheriff Schrader, leading to a hung jury and eventually a dismissal of the charges.

The Rocky Mountain News helped to spread the story of Rev. Glover’s arrest of Abe Ong, making both men famous across the state. [Rocky Mountain News]

After being released the following afternoon, Abe took it upon himself to call for the Reverend’s arrest for carrying a concealed weapon. A warrant was signed, but Mayor S. K. Walker ordered the marshal to not serve the papers. In response, Abe and his posse confronted Mayor Walker in the streets to urge him to reconsider. The argument grew heated and Abe accused the Mayor of dishonesty. According to eyewitnesses, the Mayor delivered such a forceful blow that it knocked Ong a full twenty feet away. Abe and his crew fled the scene, promising to kill Reverend Glover when they came back. “I’ll shoot on sight,” replied the Reverend when informed of the threat, “and convert him in the hospital.” Abe never gave him any trouble after that.

In October 1913, Abe was charged with another ten indictments from a Grand Jury, alongside four former county officials charged with fraud. Rather than wait to be arrested, Ong made the trip down to Grand Junction to pay a bond of $2,000 (about $62,466 adjusted for inflation), then immediately returned back to De Beque to “take care of his prosperous business.”

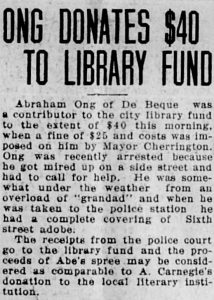

Abe donated $40 to the Library Fund in February 1914 after his arrest for public drunkenness, technically making him one of the earliest sponsors of our library. [Daily Sentinel]

Unluckily for Abe, the jury was not particularly convinced by the attorney’s argument that there was no evidence that he had been running a “disorderly house,” and he was delivered a verdict of guilty after just ten minutes of deliberation. He was sentenced to six months in county jail and was ordered to pay the costs of the prosecution. He was released in late August, and according to the Palisade Tribune, claimed “his imprisonment had been beneficial and that he would give more attention to the law’s requirements hereafter.”

Within three weeks of his release, he was once again under arrest after Sheriff Schrader raided his cigar shop in Grand Junction, but this time, he was acquitted. On November 23, his cigar shop was raided once again by Chief of Police Wallis and Policeman Allison, where they captured a barrel of Blue Ribbon beer, several bottles of beer and whiskey, and Abe’s revolver. In response, Abe tried to have the officers arrested on a charge of burglary, but the case was dismissed by the District Attorney.

Abe was busted in another raid in January 1915, this time receiving a guilty verdict and a further sentence of 6 months. In April, he led his chain gang in a strike against working on repairing roads in the Redlands. The guard attempted to threaten the prisoners with his rifle, but Abe approached with a smile and told him, “We’ve struck and we won’t work another minute, and we aren’t afraid of that little pop gun you have, either.” The guard failed to break up the strike and had to send the men back to jail.

Abe was released in July and was caught once again in August, after police intercepted a wagon filled with liquor backing into to Abe’s cigar store, and once again, he was convicted. He was again found guilty in November, then again busted in January 1916, when Abe and nine associates were arrested for contraband liquor. In this latest raid, police discovered bottles of whiskey stashed away in dresser drawers, a sewing machine, under floorboards and heaps of coal, in typewriter desks, and even under a sleeping baby resting in a carriage. The judge did not award him any leniency for his creative hiding spots, and he was sentenced to 9 months in jail, with a scathing warning that his next offense would land him in the state penitentiary.

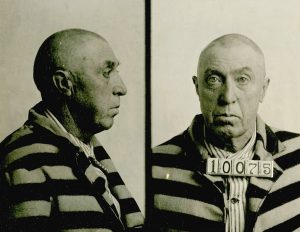

Abe Ong’s mug shot from the state penitentiary, c. 1916. [Colorado State Archives]

Records grow spottier following Abe’s release from prison, but all evidence suggests that he kept up his old habits as the nation as a whole entered its Prohibition Era. In April 1924, Abe was sentenced to ninety days in county jail for bootlegging. He returned to the state penitentiary at least two additional times, both for liquor violations. In October 1930, police raided his home in Rifle and found 251 bottles of homebrew, a barrel, and two gallons of whiskey – which Abe claimed he was just holding for a friend – and was sentenced to thirty days in jail.

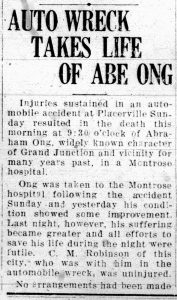

Abe Ong died on April 14, 1931 due to injuries sustained in an automobile accident. [Daily Sentinel]

Over time, Abe Ong faded into obscurity. Now, the man who once was described as having “well earned the distinction of being Mesa County’s foremost citizen” has been largely forgotten. While certainly not as notorious as Al Capone or Charles “Lucky” Luciano, Abe Ong is deserving of a place in the bootlegger hall-of-fame simply because of his obstinate determination to never stop peddling hooch. Had he lived to the end of 1933, when Prohibition was repealed, he could have retired in peace knowing that he finally won. Knowing Abe, however, he probably would have been mad that the government had finally run him out of business.

_________________

If you want to know more about Abe Ong, be sure to check out “Women, Politics, and Booze: Prohibition in Mesa County, 1908 – 1933” by Jerritt Frank from the Fall 1999 edition of the Journal of the Western Slope and the “Prohibition Punch” chapter of Wicked Western Slope by D.A. Brockett; both of which were major sources of inspiration.

For more information on Prohibition locally, check out our previous Local History Thursday on Prohibition in Mesa County. You should also take a look at Temperance and the Colorado Frontier and Ute Removal and the End of the Colorado Frontier, which include context on the temperance movement which led to Prohibition.

With that out of the way, I think I’ve had my fill on talking about Prohibition. Stay tuned for something completely different, and as always, thank you for reading.

Thank you to the Friends of Mesa County Libraries for supporting Local History blogs like these.

Thank you to the Friends of Mesa County Libraries for supporting Local History blogs like these.

Very much enjoyed your post here Kristen . I have run across his name many times in my searching through early newspapers and often wondered about the connection to law enforcement and judges. I look forward to more interesting stories.

Joe Zeni