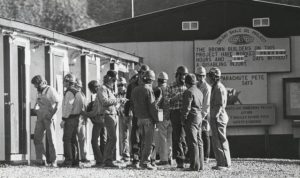

Colony Project workers line up to receive their final paychecks. Most cashed their checks, packed their belongings, and left town. [Denver Public Library Special Collections, RMN-044-8371]

This is part two in our history of the Colony Shale Oil Project and the Black Sunday oil shale bust. If you haven’t read part one, where we talk about the oil shale boom, the growth it created, and Exxon’s involvement, then you should check it out to get the full picture. We’ll pick up right where we left off.

When the news first reached Western Colorado on May 2, 1982, most reacted with disbelief. The Daily Sentinel reported groups of confused employees gathering outside of their homes in Battlement Mesa – homes that were built and financed by Exxon themselves – waiting for any news that might confirm or deny what they had heard.

“I don’t believe it.” said one man, beer in hand, standing on the lawn he had purchased only two months earlier, “They wouldn’t close the project down. Exxon’s spent millions – no billions – of dollars here. They wouldn’t just close it down.”

“I think you’re wrong, young man.” another woman told a reporter, “Look, if this project is closing, how come we just processed 40 new carpenters through the personnel office last Wednesday? It doesn’t make any sense, does it?” (The Daily Sentinel, May 3, 1982)

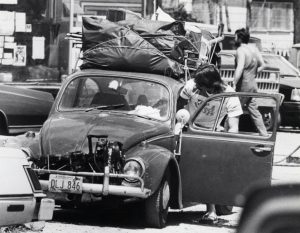

Many people didn’t wait for the dust to settle before hastily packing their belongings and leaving town. [Denver Public Library Special Collections, RMN-042-8824]

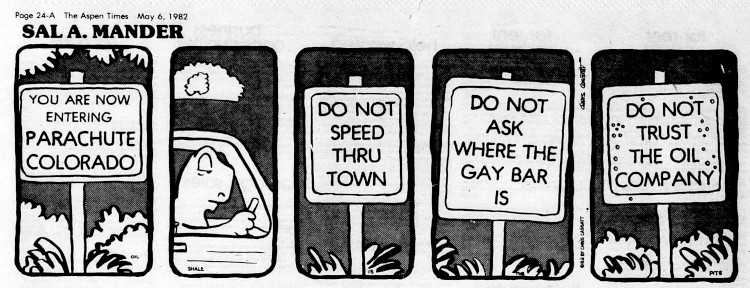

To say the news was sobering would be… well, it wouldn’t exactly be true. Laid-off workers drowned their sorrows the only way they knew how to. Pat O’Neill, owner of O’Leary’s Pub in Parachute, rushed to open his bar as soon as he heard the news, even though it was typically closed on Sunday for Catholic Mass. The pub was filled the next day by mid-afternoon.

Law enforcement geared for the worst, expecting widespread vandalism and public disturbance from disaffected workers, but aside from a few scuffles and a destroyed fence, there wasn’t too much trouble. Parachute Police Chief Steve Rhoads was content to let people blow off steam. He told the Daily Sentinel about a mid-afternoon bar check at O’Leary’s Pub where he broke up a mock kickboxing match between two barrel-chested men. He reportedly smiled when one of the combatants turned to him and said, “You want to snort some cocaine, chief?” (The Daily Sentinel, May 4, 1982)

The only thing to sell faster than liquor were moving trucks. By Monday evening, every truck and trailer rental service in Parachute and Rifle had been emptied out. Folks weren’t sticking around to see what a post-boom future looked like in Western Colorado. From 1983 to 1985, Garfield and Mesa counties lost a combined 24,000 in population, effectively undoing the growth from the boom.

Pulling up the stakes and leaving was all well and good for the “boomers” (transient workers who moved from place to place as jobs opened up), but what about the people who were here to stay? “What am I going to do with this house?” asked Tim Oster, manager of an insulation company who arrived in Battlement Mesa in the fall of 1981, “Who’s going to buy it if this town dies? I’ve got $73,000 tied up. I’m not worried about my job or if I can feed my family, but what about my house?” (The Daily Sentinel, May 4, 1982) The collapse in real estate prices hung over the region for years to follow.

Sal A. Mander cartoon by Chris Cassatt [The Aspen Times Weekly, May 6, 1982]

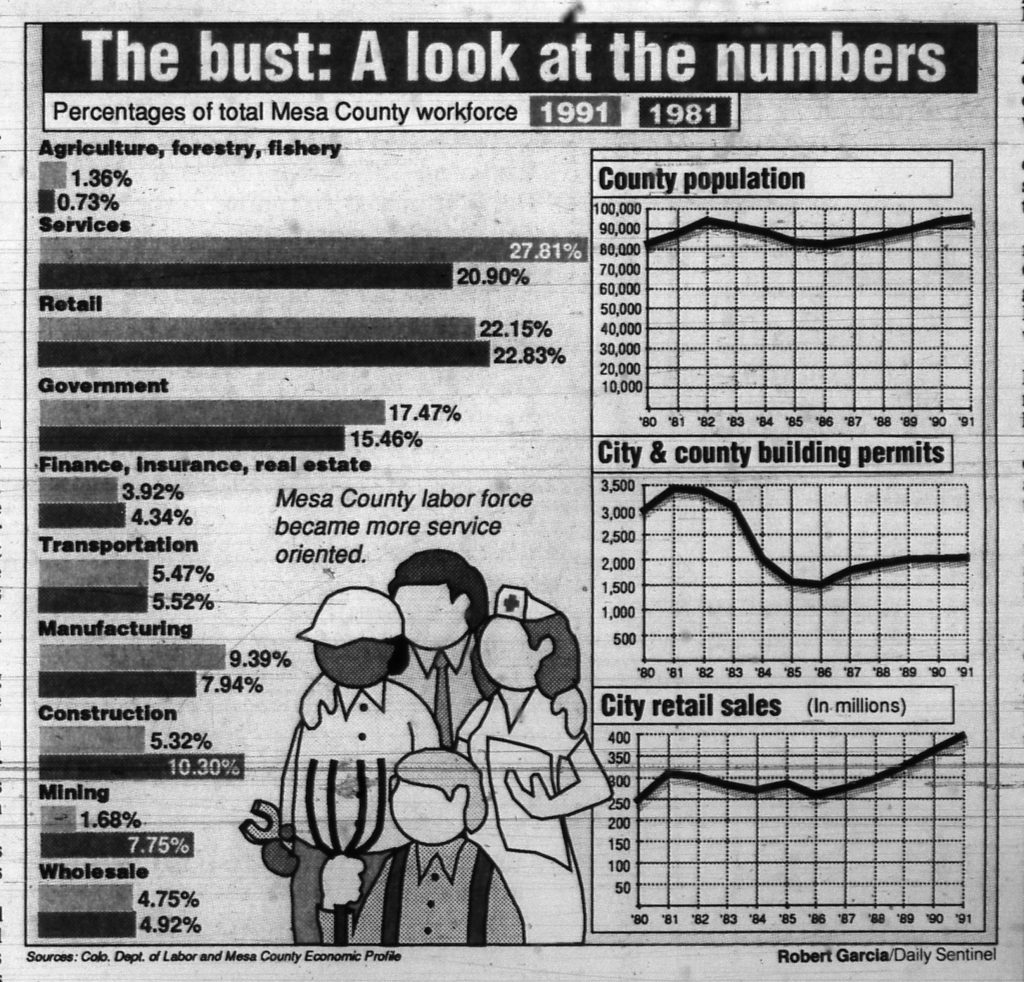

The aftershocks of economic turmoil continued to ripple for years later. By February of the following year, Mesa County reached its peak of a 15.7% unemployment rate, and Garfield County reported 15.2% unemployment that March (The Daily Sentinel, May 4, 1983). Foreclosures in Mesa County jumped from 98 in 1980 to 1042 in 1984. As an article in the 1985 Atlantic Monthly claimed, “Within four years the mortgages on one out of every twenty houses in the county were foreclosed — financial ruin on a scale not seen in most midwestern steel towns.” (Andrew Gulliford, Boomtown Blues, 186)

It should be noted that this all happened in the midst of a global recession. In 1979, the Iranian Revolution led to a sharp increase in global oil prices, which pushed already high rates of inflation over the edge. High interest rates affected industries reliant on borrowing the hardest, most notably manufacturing and construction. The Colony Project helped to insulate the Western Slope from the worst impacts of the recession, in large part because high oil prices fueled the speculation behind the boom. When oil prices shot down between 1981-1982, it caused Exxon to reevaluate its investments and pull out of the Colony Project. It was as if the dam had burst, causing three years of recession to flood the Western Slope all at once. As a result, the Western Slope remained in a depressed state even as the rest of the country rode the high highs of the mid-to-late 80’s.

This graph shows the impact that Black Sunday had on the economy of Mesa County’s from 1981-1991. [The Daily Sentinel, May 3, 1992]

Mike McEvoy, President of Palisades National Bank, offered a more cynical analysis of the recovered economy, “We’re on the comeback trail but it’s never going to be good as it was,” he told the Daily Sentinel, “We’ve made some progress but at the expense of some awfully good people and some good businesses.” (The Daily Sentinel, May 3, 1992) Indeed, it was clear to most that there would never be another oil shale boom like the one that just passed by.

Even so, there’s an argument to be made that the region is all the stronger for it 41 years later. Our economy is more diverse than ever, primarily based in service, tourism, and agriculture and balanced by a diverse energy industry. The bust brought the community together on a lot of new things too. The former director of the Art Center, Dave Davis, started Art on the Corner in 1984 in an effort to revitalize the town after the bust. It was one of the first outdoor sculpture exhibitions of its kind in the country and has inspired cities across the U.S. to host their own.

Oil shale never really recovered from the blow dealt by Black Sunday, but our regional crude oil and natural gas industries remain strong. The future also looks bright for clean energy in Colorado, with Grand Junction’s very own Colorado Mesa University leading the way in geothermal heating and cooling. Given the state’s current objective to convert to 100% renewable energy by 2040, we can expect that oil shale will likely stay buried in the ground. Still, if there’s one thing to be learned from Black Sunday, it’s that it can be hard to predict when the pendulum will suddenly swing in the other direction.

Whatever the future holds for energy production, Western Colorado is sure to play an important role. Given our region’s history, it’s reasonable to be skeptical of any grand one-size-fits-all promises to solve our energy needs, but we also shouldn’t let an overabundance of caution prevent us from embracing new developments. Whether it’s uranium, oil shale, or geothermal exchange, there will always be people invested in our abundant natural resources. If we take care to learn from our history, we can avoid making the same mistakes.

___________________________

And that’s a wrap on our history of Black Sunday! If you haven’t read part one already, then you should definitely click here to do so! You’ve probably been very confused reading part two first. I really enjoy researching and writing these deep dives into our local history, but I think next time I’ll cover something a little bit shorter.

Did we forget to mention anything important? Do you have memories of this time? Just want to share your thoughts? Let us know down in the comments.

If you’ve read this far, you’re probably pretty interested in learning more about the local history of oil shale. I encourage you to check out Andrew Gulliford’s Boomtown Blues: Colorado Oil Shale 1885-1985, and Armand de Beque and Rob Dal Porto’s lecture on the subject available through the Mesa County Oral History Project. We also have a Local History Thursday post discussing an incident from the first shale boom.

Thank you so much for reading!

Very interesting! Well written.

My family owned a restaurant in Parachute …. Oil workers were the bread and butter … when Exxon pulled out the restaurant couldn’t survive. It went from being the busiest place in town to no business. This is a great article

… would

Be great to write about the housing in Grand Junction…how they handled housing thousands of oil workers… they built

Huge trailer parks… quick to build.. almost everyone I went to school with lived in these huge trailer parks set up by Union Oil and/Or Exxon

Hi Lanelle,

Thank you so much for sharing! I would love to hear more about the restaurant your family owned and what the housing projects looked like from someone who lived there. I’m glad you enjoyed reading.

Kristen