Content Warning: This story contains graphic descriptions of violence and suffering committed against animals. Reader discretion is advised.

In the late 19th century, competition between cattlemen and sheepherders over the open range often came to a bloody head in a series of conflicts known as the Sheep Wars. There were huge fortunes to be gained in raising livestock, and the promise of steady employment bred fierce loyalty among stockmen. In the era of the unregulated open range, it was first-come-first serve when it came to grazing, and sharing that land would mean your livestock would starve due to overgrazing. This was especially true in Western Colorado, where high mountains, scarce water, and arid deserts limited available pasturage. It was here where one of the bloodiest episodes between cattlemen and sheepherders played out.

Cattlemen greatly outnumbered sheepherders on the Western Slope, possessing 100,000 heads of cattle on different ranges by 1890 (Andrew Gulliford, The Woolly West, 46), but large traveling herds of sheep sometimes numbering in the tens of thousands could quickly overwhelm any pasture. Overgrazing was a problem with both animals, but sheep could easily graze a meadow down to dirt due to their habit of pulling plants up by their roots, preventing regrowth. Sheep additionally have a scent gland in their hooves, which cattlemen erroneously believed would cause cows to avoid eating where a sheep had grazed. (The Woolly West, 48)

Sheep herders in the La Sal Mountains in eastern Utah, c. 1897 [Denver Public Library]

In November 1891, cattlemen in the Plateau Valley formed an association to protect their ranges against the “invasion of sheep.” By their second meeting, the association already had 100 members committed to use, in their words, “every legitimate means to discourage the introduction of sheep.” It may have been their public intention to exhaust every legitimate means available, but few cattlemen were willing to stop there to keep sheep out of what they considered their pastures, especially after a recession in 1893 intensified competition over the open range.

During a particularly intense stand-off in June 1893, newspapers reported that over 3,000 rounds of ammunition had been sold over the course of just a few days in De Beque as heavily armed cowboys menaced Utah sheepmen into removing their flocks. This incident ended without open conflict, but it was clear that the cattlemen were willing to intimidate and harass sheepmen to remove them, and were prepared to fight if it came down to it. The press rumbled over the possibility of an all-out war on the open range.

In April of 1894, residents in Mesa County panicked over a “monster influx” of 140,000 sheep from Thompson Springs, Utah accompanied by 50 armed guards moving across the state border to graze on Battlement Mesa. The Daily Sentinel and The Grand Valley Star-Times provided breathless coverage of the caravan of Mormon sheep, reporting on an outbreak of sheep scab among the herds and petitioning the Governor to intervene. Governor Waite issued a quarantine to prevent diseased sheep from crossing the border, but the Mormon herders were able to treat their flocks and provide a clean bill of health, delaying their procession only for a short time.

Local ranchers, outraged by their failure to keep the Mormon sheep out of Colorado, lashed out against local herders. On May 3, 1894, a group of twenty-five masked cattlemen arrived at the cabin of Frank Reed, an Anglo herder who had been raising sheep on the same range in Plateau Valley for at least eight years. They proceeded to slaughter his entire flock of 753 sheep by means of clubbing and stabbing. A rumor had circulated that Reed was working for the Utah sheepmen and was lambing their sheep on his range, an accusation that he fervently denied. A handful of the perpetrators were identified, but were ultimately acquitted of any wrongdoing.

John Hurlburt (far left) and his family on their homestead on Parachute Creek, c. 1886. [Image courtesy of the Museums of Western Colorado]

It was a sunny Monday afternoon, September 10, 1894. Carl Brown, a herder working for Mr. Hurlburt, was grazing sheep on the Roan Plateau, north of Parachute. It was a jubilant day in Grand Junction, where 10,000 visitors, including Mr. Hurlburt, were celebrating the harvest and enjoying the festivities of the annual Peach Day.

Carl Brown was sitting in his tent preparing his dinner when he heard a loud POP. He peered down to see that he had been shot in the hip. Another bullet whizzed by, barely missing his head. He hobbled out of his tent to see he was surrounded by fifty masked cowboys mounted on horseback. To his surprise, the cowboys apologized for shooting him, stating they had only fired the shots to frighten him. One of the cowboys identified himself as a doctor and proceeded to skillfully dress his wound. After Mr. Brown’s injury was treated, the cowboys proceeded to hogtie and blindfold him, forcing him to listen as they began slaughtering his flock.

“Sheep Raid in Colorado” portrayed in Harper’s Weekly, c. 1877 [Denver Public Library]

Dubbed the Peach Day Massacre, the entire incident was seemingly timed to cause the most destruction possible. On most days, there would have been two herders watching each band, but John Hurlburt had paid for his employees to join him in Peach Day festivities, leaving Mr. Brown alone to watch the flock.

When Mr. Hurlburt arrived with the sheriff, he discovered a truly horrific scene. Wading through ankle-deep pools of blood, the pair witnessed mountains of dead sheep piled as high as a man’s head. A number of sheep were still alive, bleating in pain, stumbling around with their throats slit. Mr. Hurlburt was obliged to put them out of their misery with his revolver. The only survivor, according to Diane Abraham, was a single small lamb, clinging to an outcrop on the cliff, who could not be rescued. (Diane Abraham, Bloody Grass: Western Colorado Range Wars, 1881-1934, in the Journal of the Western Slope, Spring 1991, 8)

John Hurlburt was financially ruined by the massacre. He estimated the massacre had cost him $8,000 in damages, which he sought as recourse from the Garfield County Board of Commissioners. His request was denied. He later managed to get Senator Taylor to sponsor a bill in the state legislature to recompense him for $9,530 in damages, but this too was ultimately unsuccessful.

If nothing else, the incident had certainly captured the attention of Coloradans across the state. Governor Waite offered a bounty of $500 for any information on the perpetrators, but no one was ever identified. To this day the mystery remains unsolved, but history provides a few notable clues as to the identity of at least one of the masked cowboys.

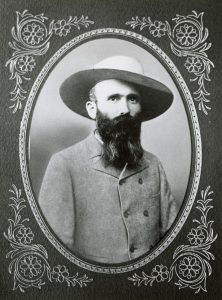

Perhaps the most noteworthy character among the cowboys was the doctor who patched up Carl Brown. There were not many medical doctors in either Garfield County or Mesa County in those early days, and fewer still who lived in the immediate vicinity and were invested in cattle ranching. All signs point to one man in particular, someone who just happens to be one of Western Colorado’s most well-known pioneers: Doctor Wallace A. E. de Beque, the founder and namesake of De Beque, CO.

Dr. Wallace A. E. de Beque, founder of De Beque, CO. [Image courtesy of the Museums of Western Colorado]

“All through his life, my father hated sheep,” he commented, “For the sheep to go to the stockyard, they had to go down the street behind our house, right by our fence, coming from Roan Creek. […] My father would hear a herd of sheep coming, and he would go out there with his revolver and he would stand by our fence, and he would position me in another place up there, with a club, and if any sheep got close to our fence, we were to see that they didn’t get on our property.”

Perhaps more revealing, however, was a story that Armand relayed about masked visitors who visited his father one evening:

“My father was sitting in his kitchen one evening, just getting through his supper, and there was a knock on the door. He went to the door, and there were two men at the door that had masks on their faces. They told my father that they wanted him to go with them ‘cause they were going to have a war with the sheepmen, and they wanted a doctor along in case anybody got hurt. And they said, ‘We know you know who we are, but if we have masks on our faces, if this comes to court, you won’t be able to swear that you saw us.’ So my father said, ‘That’s fine,’ so they went.”

It should be noted that Armand was born in 1912, so he could not have been a witness to this conversation. Still, many of the details line up well, and any discrepancies can be explained by Armand receiving this information second-hand.

“My father went with these cattlemen and they went up there and they drove these sheep over the cliff there, so to speak, and there was no — I guess there was no shooting. My father never mentioned that there had been and he didn’t have to patch anybody up, and he came back home.”

It’s not much of a stretch to suggest that he simply didn’t mention that someone actually had been shot, as a father embellishing details to avoid upsetting his son might do. In fairness, it’s also possible that this particular visit was for a different raid, such as the one involving Frank Reed’s sheep. Armand de Beque’s description suggests that his father was likely to have been the medic who patched up Carl Brown during the Peach Day Massacre, but there is no direct corroboration linking him to the scene of the crime.

At minimum, it is clear that Dr. De Beque had significant involvement with the masked marauders who waged a campaign of terror on sheepmen in Western Colorado. With some small assumptions, it can be asserted that one of Mesa County’s foremost pioneers was directly involved in one of the most brutal massacres of livestock over the open range in Colorado, in what may have been the single most deadly day in the history of the Western Slope.

Charlie Glass’s headstone in Elmwood Cemetery in Fruita, CO. Charlie Glass is famous for becoming the first black citizen to be buried in Fruita, at the time a sundown town. [My Photo]

In 1934, the passage of the Taylor Grazing Act settled the range wars for good. The bill was introduced by Edward T. Taylor, a Congressman from Glenwood Springs, roughly 50 miles away from the site of the Peach Day Massacre. The bill empowered the Department of the Interior to regulate grazing districts on public lands, granting ranchers use of the land through permits. While stockmen balked over needing to pay a fee to graze their livestock, the permitting system eliminated direct competition and allowed for regulation to prevent overgrazing and watershed degradation.

Animosity between cattlemen and sheepherders is largely a thing of the past. Much of this has to do with management of rangelands, but another factor worth considering is the large decline in the number of sheep in general in the West. America’s taste for beef has only grown since the late nineteenth century, and many sheepmen simply switched to raising cattle instead. It’s a tough job, even when no one’s shooting at you. On State Highway 13 between Rifle and Meeker, where 30,000-40,000 sheep once grazed, there are now only 5,000 (The Woolly West, 277).

The masked marauders who terrorized sheepmen, destroyed property, and massacred innocent livestock belong to the same lineage of militant organized terror that defined some of the worst hate organizations in American history. The violence that characterized the open range in the 1890s marked a low point for relations between cattlemen and sheepherders in Western Colorado. What started as competition over limited resources quickly grew into a social panic fueled by prejudice, fear mongering, and sensationalism. Today, stockmen can work an honest living without fearing attacks from their neighbors.

_________________

Full disclosure, I spent much of my time growing up in Grand Junction on a cattle ranch owned by my grandparents. I also have family members in New Mexico who were at one point involved in herding sheep. That said, I don’t think I particularly have any advanced knowledge on what it takes to raise livestock, so if I got anything wrong, please let me know in the comments!

There was so much to talk about here that I unfortunately did not have the opportunity to cover. Frank Reed, John Hurlburt, and Carl Brown were just three notable victims, but they were far from the only locals who were impacted by the Sheep Wars in the mid-1890s. This conflict spanned across nearly every western state over a course of sixty years, so there is always more to tell.

If you’d like to learn more about the local history of the Sheep Wars, I highly recommend you read The Woolly West: Colorado’s Hidden History of Sheepscapes by Andrew Gulliford, who has been cited in Local History Thursday many times by now. I also recommend Diane Abraham’s “Bloody Grass: Western Colorado Range Wars, 1881-1934,” in the Journal of the Western Slope, Vol. 6, Spring 1991. You should also take a look at the Mesa County Oral History Project, which includes interviews like the one featured here with Armand de Beque.

A sincere thanks to the Museums of Western Colorado and the Denver Public Library for providing images.

Thank you for reading!

Thank you to the Friends of Mesa County Libraries for supporting Local History blogs like these.

Thank you to the Friends of Mesa County Libraries for supporting Local History blogs like these.

Awesome!

Kristen,

What a fascinating story, I really enjoyed it and learned so much about this aspect of local history. More please

Excellent!

So very interesting! Thank you! And I agree with Joe, MORE Please!