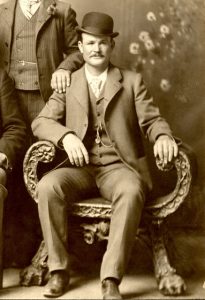

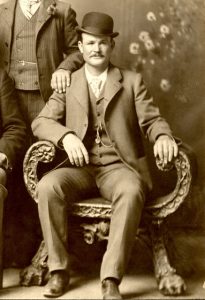

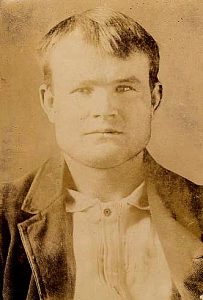

Iconic “Fort Worth Five” photograph of Butch Cassidy used by the Pinkerton Detective Agency, c. 1900. [Public Domain Image]

It goes without saying, but Butch Cassidy was a real fascinating character. Despite being one of the Old West’s most notorious outlaws, he’s almost talked about as a sort of folk hero. Unlike many other outlaws and gangsters of American past, like Jesse James and Al Capone, Butch Cassidy is firmly established within an almost romanticized mythology of the West. He never shot anyone, nor did he rob anyone who wasn’t already rich (though members of his gang, The Wild Bunch, did not stick as closely to this code of ethics). He was a legend within his own time, too. Historian Charles Kelly, who penned one of the earliest biographies of Cassidy in 1938, wrote “All the old-timers interviewed for this biography, including officers who hunted him, were unanimous in saying ‘Butch Cassidy was one of the finest men I knew.’” (Charles Kelly,

The Outlaw Trail, 4) Even before Paul Newman charmed audiences in

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Cassidy was already extremely captivating figure within American folklore.

It probably helped that he didn’t stick to one place. As an outlaw, he was constantly on the run or looking for a new score. Thus, historians from San Antonio to Montpelier all have pieces to contribute to his story. Western Colorado is no exception. In fact, Butch Cassidy’s journey from honest man to criminal outlaw happened right here on the Western Slope.

Robert Leroy Parker, later known as Butch Cassidy, was born in 1866 to a family of Mormon pioneers in Beaver Valley, Utah Territory. As a teenager, he worked the family ranch and was known as a hard worker and an excellent horseman. During this time, he befriended a man named Mike Cassidy, a drifter and cattle rustler. Butch looked up to Mike Cassidy as a sort of gentleman outlaw, and adopted his last name. In turn, Mike mentored the young Butch, teaching him everything from cowboy chores, survival tips, and shooting. He probably picked up the nickname ‘Butch’ from working as a butcher as a young adult.

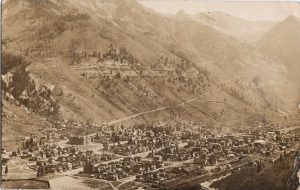

By the time Butch turned 18, Mike Cassidy had drifted elsewhere (probably fleeing to Mexico to escape the law). Feeling trapped working menial jobs in Utah, he decided to leave home and seek out a new life. He settled around Telluride and worked various odds and ends to get by. Telluride had a reputation as a raucous mining town filled with unruly miners and cowboys attracted by the large quantities of cash and gold running through town. It was a common joke that the name Telluride came from “To Hell You Ride,” referring either to the treacherous pass through the San Juans into town or to the town’s rowdy locals. Either way, that nickname was appropriate for Butch, who arrived in Telluride as Robert Parker, an upright man with Mormon upbringing, and who would eventually leave as a wanted outlaw.

Butch tried his best to make an honest living through various ranching and mining gigs, but even when he kept his nose clean, he couldn’t escape trouble with the law. In 1885, he was accused of stealing a colt from a ranch outside of Telluride. It was his family’s horse, and Butch had simply pastured it at the ranch. The rancher offered to buy the horse, but Butch refused. The next time he arrived to work with his colt, he was arrested and taken to a cell in Montrose. Neighbors of the rancher claimed that the young colt had belonged to the rancher for quite some time, while Butch failed to produce any paperwork to prove ownership. When his father arrived in Montrose to testify that the colt belonged to him, he found Butch reclining in his cell reading a magazine with the door wide open. The authorities supposedly knew he wouldn’t escape, and his honest character was later confirmed in court, where he was acquitted of any wrongdoing. His father implored him to return to the family farm in Utah, but Butch refused.

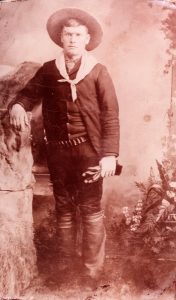

Many locals spent their paychecks gambling and drinking in Telluride’s many saloons. Pictured is the Cosmopolitan, c. 1910. [Public Domain Image]

He continued to make a modest income through hard labor, but he had an incorrigible habit of drinking and gambling away his earnings. He made friends with a fellow by the name of Matt Warner, who was a former cattle rustler who also came from Mormon roots in Utah. He introduced Butch to another outlaw, Tom McCarty, and the three of them got involved in horse racing. Butch was an excellent racer and made the trio a small fortune, but he was perhaps too excellent. Before long, nobody would dare challenge him to a race.

With that source of revenue dried up, Butch and Matt went back to work at the Spectator Ranch owned by Harry Adsit, about 40 miles west of Telluride. This didn’t last very long. Butch had constantly found himself back doing menial ranch work – the very thing he had been trying to escape since he left his home in Utah. Maybe it was time for a change in career. Maybe it was time to make some real cash. The duo requested their final wages from Harry Adsit and made their way to Tom McCarty’s cabin in Cortez to plot their next move.

On June 24, 1889, Butch Cassidy, Matt Warner, and Tom McCarty arrived back in Telluride for their final visit. One of the men walked into the San Miguel Valley Bank, handed the clerk a check, and grabbed him by his neck as he bent down to inspect it, slamming him into the counter at gunpoint. The remaining men entered the bank and cleaned it of loose cash. Witnesses reported the “daring cowboys” scouting the bank for hours, waiting until the clerk had been left alone. When they exited with the cash, they “spurred their horses into a gallop, gave a yell, discharged their revolvers and dashed away.” (

Rocky Mountain News Daily, June 27, 1889) By the time a sheriff’s posse had been formed – notably without the Town Marshall Jim Clark – the boys were long gone. Marshall Clark

later admitted the robbers left him $2,200 in exchange for leaving town the day of the holdup. Furthermore, the telegraph wire connecting Telluride to Dallas had been cut before the robbery, complicating communication in-and-out of town (

Rocky Mountain News Daily, June 27, 1889). All told, the score was worth $20,750, or over half a million in today’s money.

They probably would have gotten away with it had they not been identified by a rancher while fleeing west – possibly their former boss, Harry Adsit. In his memoir, Matt Warner wrote “Right at the point we broke with our half-outlaw past, became real outlaws, burned our bridges behind us, and had no way to live except by robbing and stealing.” (Matt Warner, Last of the Bandit Raiders, printed in The Last Outlaws by Thom Hatch) Butch Cassidy, with a sheriff’s posse in pursuit, dug in his spurs and left his previous life behind.

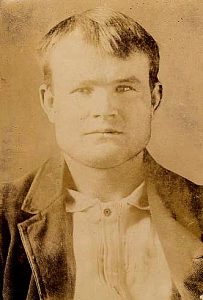

Butch Cassidy’s 1894 mugshot from Wyoming State Prison. It was the first and only time he was imprisoned. [Public Domain Image]

I can’t help but remember that nickname for Telluride, “To Hell You Ride,” and how it relates to the almost mythical status that Butch Cassidy achieved. If you’ll permit an offbeat analogy to Classical mythology, it’s common for heroes in those stories to make literal journeys into the underworld, such as the case for Odysseus and Orpheus. During these journeys, the hero typically undergoes a figurative death of the old self and rebirth into a new role. It’s a common enough theme in Greek myth that there’s actually a word for it: katabasis. If we view Butch Cassidy’s journey into Telluride and dramatic turn to criminality as a story of katabasis, then it helps to explain the near-mythological role that he’s acquired in American culture. It also suits him as more of an antihero, since most protagonists in Greek myths tend to be pretty morally dubious characters.

Is it a bit of a stretch to compare a fun story about a bank heist to the mythical descent into the underworld? Maybe! I think with any mythology, whether based in historical fact or legend, your interpretation is what gives it meaning. Just as Greek myths reflected their values, we can see how the mythology surrounding Butch Cassidy reflects some of the uniquely modern values that define America. He was a man who lived and died by his own terms, whether they were good, bad, or ugly – and what could be more American than that?

Of course, Butch Cassidy’s legend had only just started when he robbed that bank in Telluride, but we’re going to have to cut it here. If you want to read how the rest of his story goes, I recommend reading The Outlaw Trail by Charles Kelly, The Last Outlaws by Thom Hatch, and Butch Cassidy: The True Story of an American Outlaw by Charles Leerhsen, which were the main sources used for researching this. You should also definitely watch Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969), which was partially filmed along the narrow-gauge railway between Durango and Silverton.

Thank you for reading!

Good information! Sometime go read the large stone “historic marker” on Butch Cassidy at the state welcome center at Fruita. Mostly incorrect.